| w | statement | H / L | r | RC ? |

| 0.80 | When I was learning to read at school, I often felt I was slower than others in my class | H | 0.62 | - |

| 0.53 | My spelling is generally very good | L | - 0.51 | RC |

| 0.70 | I find it very challenging to manage my time efficiently | H | 0.15 | - |

| 0.71 | I can explain things to people much more easily verbally than in my writing | H | 0.45 | - |

| 0.57 | I think I am a highly organized learner | L | - 0.08 | - |

| 0.48 | In my writing I frequently use the wrong word for my intended meaning | H | 0.73 | - |

| 0.36 | I generally remember appointments and arrive on time | L | -0.10 | - |

| 0.75 | When I'm reading, I sometimes read the same line again or miss out a line altogether | H | 0.67 | - |

| 0.76 | I have difficulty putting my writing ideas into a sensible order | H | 0.70 | - |

| 0.80 | In my writing at school, I often mixed up similar letters like 'b' and 'd' or 'p' and 'q' | H | 0.60 | - |

| 0.57 | When I'm planning my work I use diagrams or mindmaps rather than lists or bullet points | neutral | 0.47 | - |

| 0.75 | I'm hopeless at remembering things like telephone numbers | H | 0.44 | - |

| 0.52 | I find following directions to get to places quite straightforward | L | -0.08 | - |

| 0.57 | I prefer looking at the 'big picture' rather than focusing on the details | neutral | 0.24 | - |

| 0.63 | My friends say I often think in unusual or creative ways to solve problems | H | 0.41 | - |

| 0.52 | I find it really challenging to make sense of a list of instructions | H | 0.54 | - |

| 0.52 | I get my 'lefts' and 'rights' easily mixed up | H | 0.45 | - |

| 0.70 | My tutors often tell me that my essays or assignments are confusing to read | H | 0.58 | - |

| 0.64 | I get in a muddle when I'm searching for learning resources or information | H | 0.64 | - |

| 0.72 | I get really anxious if I'm asked to read 'out loud' | H | 0.55 | - |

discourse study-blog | resources | lit review maps | profiles

enquiry dysdefs QNR | dysdims QNR | research QNR

thesis overview | literature | research design | analysis & discussion | closing reflections

Draft (2017-18)

Draft (2017-18)

Research design

This section opens by refreshing the aims and objectives of the project and outlining the principal elements of the research design.

This is followed by a reminder about the metrics that are used in the data collection and subsequently in the quantitative analysis, and summarizes why these were appropriate in the context of the theoretical underpinnings of the project. A short section follows which reiterates my intrinsic stance on the project, but which also states my position on research methodology processes in level 8 study and how this has impacted on not only the design of the data collection tools but also on my own personal learning development journey.

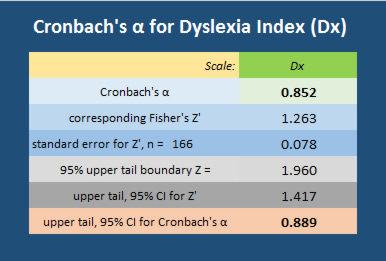

The methodology for the project is explained through use of a workflow chronology as I considered this to be the most expedient way to document the journey from research question to data collection and analysis. Particular attention is given to this project's unique perspective on quantifying dyslexia-ness in higher education students with a lengthy report being provided which describes the process of development of the Dyslexia Index Profiler that has been used to gauge dyslexia-ness in this study, this being the independent variable in the quantitative analysis. This includes an account of the processes applied to determine levels of internal reliability consistency and how this influenced the analysis->re-analysis cycle that was used to try to arrive at the most dependable analysis outcomes.

In the Methods section which follows, an account is provided about how the research questionnaire was constructed and deployed which includes reports of difficulties and challenges encountered - technical, ethical and practical - and how these were overcome. Difficulties that the use of Likert-style items and scales present to the quantitative researcher are briefly discussed which outline the statistical tensions created through the conventional use of fixed anchor-point scales, the non-parametric data that these provide and a tendency for researchers to manipulate such data so that parametric statistical tests can be applied, a practice which it is argued can render the meaning derived from such data analysis procedures as dubious in many circumstances. Hence particular attention is paid to explaining how I tried to mitigate these effects through the development of continuous-range scales in the research questionnaire as a mechanism to replace traditional, discrete, fixed anchor-points in the Likert-scale items that I used.

This section concludes by describing the process of multifactoral analysis that has been applied to data collected for both metrics, and especially for the Dyslexia Index metric, relating the pertinence of this given that dyslexia in higher education contexts is increasingly being researched through the lens of multifactorialism. Attention is given to reporting why this was considered useful and also how it enabled the data to be iteratively analysed-re-analysed to try to identify more specifically the combinations of factors of Dyslexia Index and of Academic Behavioural Confidence that were the most influential in explaining differences in academic confidence between dyslexic, non-dyslexic and quasi-dyslexic students at university.

- ABSTRACT

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PROJECT OVERVIEW

- RESEARCH QUESTIONS

- STANCE

- RESEARCH IMPORTANCE

-

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

-

DYSLEXIA

DYSLEXIA

- A complex phenomenon or a psuedo-science?

- Dyslexia: the definition issues

- Dyslexia as a multifactoral difference

- Disability, deficity, difficulty, difference or none of these?

- Labels, categories, dilemmas of difference, inclusivity

- Impact of the process of identification

- To Identify or Not To Identify? - that is the question

- Measuring dyslexia - "how dyslexic am I?"

-

ACADEMIC CONFIDENCE - theoretical foundations of the construct

ACADEMIC CONFIDENCE - theoretical foundations of the construct

-

ACADEMIC SELF-EFFICACY - the parent construct for academic confidence

ACADEMIC SELF-EFFICACY - the parent construct for academic confidence

- The construct of academic self-efficacy

- The relationships between academic self-efficacy and academic achievement

- Confidence as a learning attribute

- The location of academic confidence within the construct of academic self-efficacy

- Academic Behavoural Confidence

- Use of the ABC scale in this research project

-

-

RESEARCH DESIGN

RESEARCH DESIGN

-

RESULTS, ANALYSIS and DISCUSSION

RESULTS, ANALYSIS and DISCUSSION

- LIMITATIONS

- CONCLUSIONS

- DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

- REFERENCES

-

APPENDICES

APPENDICES

Research Design

Research Design Section Contents:

- OVERVIEW

- METHODOLOGY

- Stance

- Workflow chronology

- The preceding MSc small-scale enquiry

- Defining dyslexia: the professional practitioners' view

- Existing dyslexia evaluators and identification processes - why these were dismissed

- Rationale for developing the Dyslexia Index Profiler

- Operationalizing academic confidence through the Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale

- Collecting information - the rationales, justifications and challenges

- METHODS

- Outline

- Establishing the datapool; sample sizes and statistical power; participant recruitment

- Procedures for data collection, collation and pre-analysis

- Designing and building a web-browser-based electronic questionnaire

- Questionnaire design rationales

- Questionnaire construction and the HTML5 scaffolding

- Questionnaire sections and components

- participant demographics

- gauging academic confidence: the ABC Scale

- the 6 psycho-sociometric constructs

- gauging dyslexia-ness: the Dyslexia Index Profiler

- supporting qualitative data

- The ABC Scale (justification for use)

- Development and construction of the Dyslexia Index (Dx) Profiler:

- The final, published version of the research questionnaire

- Designing and building a web-browser-based electronic questionnaire

- Statistical tools and processes:

- Use of the t-test in preference to ANOVA

- Effect size

- Principal Component Analysis

- Research Design section summary

Overview

The aims and objectives of this research project together with the clear research questions have been set out in the opening sections of this thesis.

The aims and objectives of this research project together with the clear research questions have been set out in the opening sections of this thesis.

This section, reporting on the Research Design, describes the blueprint for the strategic and practical processes of the project that were informed at the outset by the researcher's previous Master's dissertation, subsequently by the relevant literature - including identifying where gaps in existing knowledge became evident - and not least by the researcher's deep desire, as a learning practitioner in higher education, to explore how dyslexic students perceive the impact of their dyslexia on their study behaviours, attitudes and processes at university - collectively gauged through the lens of academic confidence - in comparison with their non-dyslexic peers. A particular focus has been to consider how an individual's knowledge and awareness of their dyslexia can be a significant factor, possible more so than the challenges and learning issues that their dyslexia may present in a learning environment that remains steadfastly literacy-based. The research design has attempts to address this by comparing levels of academic confidence between dyslexic students and their quasi-dyslexic peers. In addition to conducting a study in this under-researched area which is highly interesting in itself, the driving rationale has been that the outcomes of the research might usefully contribute to the gathering discourse about how knowledge acquisition, development and creation processes can be transformed in higher education in ways that more significantly adopt principles of equity, social justice and universal design (Lancaster, 2008, Passman & Green, 2009, Edyburn, 2010, Cavanagh, 2013), because it is argued that this may be a comprehensive learning solution that may mitigate or even nullify the impact of a dyslexic learning differences at university. This is approach is supported by an argument gaining traction that dyslexia may now be best considered as an alternative form of information processing (Tamboer et al, 2014) rather than a learning disability (eg: Heinemann et al, 2017, Joseph et al, 2016, amongst numerous other studies).

Descriptions are provided about how practical processes have been designed and developed to enable appropriate data sources to be identified and how data has been collected, collated and analysed so that the research questions can be properly addressed. The rationales for research design decisions are set out and justified, and where the direction of the project has diverted from the initial aims and objectives, the reasons for these changes are described including the elements of reflective processes that have underpinned project decision-making and re-evaluation of the focus of the enquiry where this has occurred. The originality of the research rationale will be emphasized and justification made as to the equally original final presentation of the project outcomes where this will be a combination of this traditionally-written thesis and an extensive suite of webpages that have been constructed by the researcher as part of the learning development process that this doctorate-level study has contributed to. The project webpages have served as a sandbox for project ideas and development of some of the technical processes, particularly related to data collection and for diagramatically representing data outputs. The webpages have also diarized the project, contain a reflective commentary on the project's progress throughout its 3-year timescale through a Study Blog; and contain, present and visualize the data collected. An electronic version of the final thesis is published on the project webpages, notably so that pertinent links to supportive, online material contained elsewhere on the webpages can be easily accessed by the reader.

Design focus

This primary research project has taken an explorative design focus because little is known about the interrelationships between the key parameters being investigated and so no earlier model has been available to provide guidance. The main emphasis has been to devise research processes which are able to establish empirical evidence to support previously anecdotally observed features of study behaviour and attitudes to learning amongst the dyslexic student community at university. These were study characteristics that appeared to the researcher to be driven more so by students' feelings about their dyslexia and what being identified as 'dyslexic' meant to their study self-identity rather than ones that might be expected to be more directly influenced by the obstacles and impediments to successful academic study, apparently attributable to their dyslexia, when functioning in a literacy-based learning environment. This was first explored in the Master's research dissertation (Dykes, 2008) which preceded this PhD project, is available here, and which has contributed to this current project as a virtual pilot study.

The fundamental objective has been to establish a sizeable research group datapool that comprised two principal subgroups: the first was to be as good a cross-section of higher education students as may be returned through voluntary participation in the project; the second was to be a control group of students known to have dyslexic learning differences by virtue of a) acquiring them as participants through a request targeted specifically at the university's dyslexic student community, and b) through their corresponding self-disclosure in the project questionnaire. In this way, it was felt that it could be assumed that students recruited from this cohort will previously have been formally identified as dyslexic through one or more of the currently available processes, for example as an outcome from an assessment by an educational psychologist either prior to, or during their time at university. Subsequently, the research aim was twofold: firstly to acquire a sense of all research participants' academic confidence in relation to their studies at university; secondly to establish the extent of all participants' 'dyslexia-ness' and this has been a key aspect of the project design because from this, it was planned that students with dyslexia-like profiles - marked by their high levels of dyslexia-ness - might be identified from the research subgroup of supposedly non-dyslexic students. Quantitative analysis of the metrics used to gauge these criteria have addressed the primary research questions which hypothesize that knowing about one's dyslexia may have a stronger negative impact on academic confidence than not knowing that one may have learning differences typically associated with dyslexia. Given that this is established, it will be suggesting that labelling a learner as dyslexic may be detrimental to their academic confidence in their studies at university, or at best, may not be as useful and reliable as previously believed (Elliott & Grigorenko, 2014).

The research design devised an innovative process for collecting original data by utilizing recently developed enhanced electronic (online) form design processes (described below), analysed it and interpreted the analysis outcomes in relation to the research questions posed at the outset and to existing literature. The research participants were all students at university and no selective nor stratified sampling protocols were used in relation to gender, academic study level or study status - that is, whether an individual was a home or overseas student - although all three of these parameters were recorded for each participant respondent and this data has been used throughout the analysis and discussion when considered apposite. For students recruited into the dyslexic students research subgroup, information was also collected in the questionnaire which recorded how these students learned of their dyslexia because it was felt that this may be pertinent to the discussion later relating to the effects of stigmatization on academic study. A dissemination of the results, together with a commentary is presented below and incorporated into the discussion section of this thesis where this has been helpful in trying to understand what the outcomes of the data analysis mean. It is anticipated that a more comprehensive analysis and discussion about this aspect of the study may be warranted later as a development of this current project.

The research design has adopted a mixed methods approach although the main focus has been on the quantitative analysis of data collected through the project's participant self-report questionnaire. The questionnaire has been designed and developed for electronic deployment through the research project's webpages and participants were recruited voluntarily on the basis of responding to an intensive period of participant-request publicity kindly posted on the university's main, student-facing webpages for a short period during the academic year 2015-16, and also through the researcher's home-university Dyslexia and Disability Service student e-mail distribution list. The raw score data was collected in the questionnaire using a Likert-style item scales although the more conventionally applied, fixed anchor point scale items, typically using 5 or 7 anchor-points, have been discarded in favour of a continuous scale approach which has been uniquely developed for this project by taking advantage of new online form processes now available for incorporation into web-browser page design. The rationale for adopting continuous Likert scale items has been to try to mitigate the typical difficulties associated with anchor-point scales where the application of parametric statistical processes to non-parametric data is of questionable validity because data collected through typically 5- or 7-point scales needs to be coded into a numerical format to permit statistical analysis. The coding values used are therefore arbitrary and coarse-grained and hence controversy relates to the dilemma about using parametric statistical analysis processes with what is effectively non-parametric data - that is, it is discrete, interval data rather than continuous. (Jamieson, 2004, Pell, 2005, Carifio & Perla, 2007, Norman, 2010, Brown, 2011, Murray, 2013). The advent of this relatively new browser functionality has seen electronic data-gathering tools begin to use input-range sliders more readily, especially in the collection of measurements of constructs that are representative individual characteristics, typically personality or other psychological characteristics following additional evidence that doing so can also reduce the impact of input errors (Ladd, 2009). Through using input-range slider functionality this is addressing many of the issues in the parametric/non-parametric debate because the outputs generated, although technically still discrete because they are integer values, nevertheless provide a much finer grading and hence may be more justifiably used in parametric analysis.

The research design has adopted a mixed methods approach although the main focus has been on the quantitative analysis of data collected through the project's participant self-report questionnaire. The questionnaire has been designed and developed for electronic deployment through the research project's webpages and participants were recruited voluntarily on the basis of responding to an intensive period of participant-request publicity kindly posted on the university's main, student-facing webpages for a short period during the academic year 2015-16, and also through the researcher's home-university Dyslexia and Disability Service student e-mail distribution list. The raw score data was collected in the questionnaire using a Likert-style item scales although the more conventionally applied, fixed anchor point scale items, typically using 5 or 7 anchor-points, have been discarded in favour of a continuous scale approach which has been uniquely developed for this project by taking advantage of new online form processes now available for incorporation into web-browser page design. The rationale for adopting continuous Likert scale items has been to try to mitigate the typical difficulties associated with anchor-point scales where the application of parametric statistical processes to non-parametric data is of questionable validity because data collected through typically 5- or 7-point scales needs to be coded into a numerical format to permit statistical analysis. The coding values used are therefore arbitrary and coarse-grained and hence controversy relates to the dilemma about using parametric statistical analysis processes with what is effectively non-parametric data - that is, it is discrete, interval data rather than continuous. (Jamieson, 2004, Pell, 2005, Carifio & Perla, 2007, Norman, 2010, Brown, 2011, Murray, 2013). The advent of this relatively new browser functionality has seen electronic data-gathering tools begin to use input-range sliders more readily, especially in the collection of measurements of constructs that are representative individual characteristics, typically personality or other psychological characteristics following additional evidence that doing so can also reduce the impact of input errors (Ladd, 2009). Through using input-range slider functionality this is addressing many of the issues in the parametric/non-parametric debate because the outputs generated, although technically still discrete because they are integer values, nevertheless provide a much finer grading and hence may be more justifiably used in parametric analysis.

In addition to recording value scores, research participants were also encouraged to provide qualitative data if they chose to, which has been collected through a 'free-text' writing area provided in the questionnaire. The aim has been to use these data to add depth of meaning to the hard outcomes of statistical analysis where this has been considered helpful and appropriate.

This method of data collection has been chosen because self-report questionnaires have been shown to provide reliable data in dyslexia research (eg: Tamboer et al, 2014, Snowling et al, 2012); because it was important to recruit participants widely from across the student community of the researcher's home university and if possible, from other HE institutions (although only two others responded to the invitation to participate); because it was felt that participants were more likely to provide honest responses in the questionnaire were they able to complete it privately, hence avoiding any issues of direct researcher-involvement bias; and because the remoteness of the researcher to the home university would have presented significant practical challenges were a more face-to-face data collection process employed.

So as to encourage a good completion rate, the questionnaire was designed to be as simple to work through as possible whilst at the same time eliciting data covering three broad areas of interest. Firstly, demographic profiles were established through a short, introductory section that collected personal data such as gender, level of study, and particularly whether or not the participant experienced any specific learning challenges; the second section presented verbatim the existing, standardized Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale as developed by Sander & Sanders (2006, 2009) as the metric for gauging participants' academic confidence that has been tested in other studies researching aspects of academic confidence in university students (eg: Sander et al, 2011, Nicholson, et al, 2013, Hlalele & Alexander, 2011). Lastly, a detailed profile of each respondent's study behaviour and attitudes to their learning has been collected and this section formed the bulk of the questionnaire. The major sub-section of this has been the researcher's approach to gauging the 'dyslexia-ness' of the research participants and care has been taken throughout the study to avoid using value-laden, judgmental phraseology such as 'the severity of dyslexia' or 'diagnosing dyslexia' not least because the stance of the project has been to project dyslexia, such that it might be defined in the context of university study, as an alternative knowledge acquisition and information processing capability where students presenting dyslexia and dyslexia-like study profiles might be positively viewed as being neurodiverse rather than learning disabled.

Metrics

Academic confidence has been assessed using the existing, Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale because there is an increasing body of research that has found this to be a good evaluator of academic confidence presented in universlty-level students' study behaviours. Secondly, no other metrics have been found that explicitly focus on gauging confidence in academic settings (Boyle et al, 2015) although there are evaluators that measure self-efficacy and more particularly academic self-efficacy, which, as described earlier, is considered to be the umbrella construct that includes academic confidence. Hence, the Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale is particularly well-matched to the research objectives of this project and comes with an increasing body of previous-research credibility to support its use in the context of this study. A more detailed profile of the ABC Scale has been discussed earlier.

Dyslexia-ness has been gauged using a profiler designed and developed for this project as a dyslexia disrciminator that could identify, with a sufficient degree of construct reliability, students with apparently dyslexia-like profiles from the non-dyslexic group. It is this subgroup of students that is of particular interest in the study because data collected from these participants were to be compared with the control subgroups of students with identified dyslexia and students with no indication of dyslexia. For the purposes of this enquiry, the output from the metric has been labelled as Dyslexia Index (Dx), although the researcher acknowledges a measure of disquiet at the term as it may be seen as contradictory to the stance that underpins the whole project. However, Dyslexia Index at least enables a narrative to be contructed that would otherwise be overladen with repeated definitions of the construct and process that has been developed.

Dyslexia-ness has been gauged using a profiler designed and developed for this project as a dyslexia disrciminator that could identify, with a sufficient degree of construct reliability, students with apparently dyslexia-like profiles from the non-dyslexic group. It is this subgroup of students that is of particular interest in the study because data collected from these participants were to be compared with the control subgroups of students with identified dyslexia and students with no indication of dyslexia. For the purposes of this enquiry, the output from the metric has been labelled as Dyslexia Index (Dx), although the researcher acknowledges a measure of disquiet at the term as it may be seen as contradictory to the stance that underpins the whole project. However, Dyslexia Index at least enables a narrative to be contructed that would otherwise be overladen with repeated definitions of the construct and process that has been developed.

Designing a mechanism to identify this third research subgroup of quasi-dyslexic students has been one of the most challenging aspects of the project. It was considered important to develop an independent means for quantifying dyslexia-ness in the context of this study in preference to incorporating existing dyslexia 'diagnosis' tools for two reasons: firstly, an evaluation that used existing metrics for identifying dyslexia in adults would have been difficult to use without explicitly disclosing to participants that part of the project's questionnaire was a 'test' for dyslexia. It was felt that to otherwise do this covertly would be unethical and therefore unacceptable as a research process; secondly, it has been important to use a metric which encompasses a broader range of study attributes than those specifically and apparently affected by literacy challenges not least because research evidence now exists which demonstrates that students with dyslexia at university, partly by virtue of their higher academic capabilities, many have developed strategies to compensate for literacy-based difficulties that they may have experienced earlier in their learning histories. This has been discussed earlier in this thesis report. But also because in higher education contexts, research has also revealed that other aspects of the dyslexic self can impact significantly on academic study and that it may be a mistake to consider dyslexia to be only a literacy issue or to focus on cognitive aspects such as working memory and processing speeds (Cameron, 2015). In particular, those processes which enable effective self-managed learning strategies to be developed need to be considered (Mortimore & Crozier, 2006), especially as these are recognized as a significant feature of university learning despite some recent research indicating at best marginal, if not dubious, benefits of self-regulated learning processes when compared with traditional learning-and-teaching structures (Lizzio & Wilson, 2006). Following an inspection of the few, existing dyslexia diagnosis tools considered applicable for use with university-level learners (and widely used), it was concluded that these were flawed for various reasons (as discussed earlier) and unsuitable for inclusion in this project's data collection process. Hence, the Dyslexia Index Profiler has been developed and, as the analysis report details below, appears to have fulfilled its purpose for discriminating students with dyslexia-like study characteristics from others in the non-dyslexic subgroup.

It is important to emphasize that the purpose of the Dyslexia Index Profiler is not to explicitly identify dyslexia in students, although a subsequent project might explore the feasibility of developing the profiler as such. The purpose of the Profiler has been to find students who present dyslexia-like study profiles such that these students' academic confidence could be compared with that of students who have disclosed an identified dyslexia - hence addressing the key research question relating to whether levels of academic confidence might be related to an individual being aware of their dyslexia or dyslexia-like attributes. From this, conjecture about how levels of academic confidence may be influenced by the dyslexia label may be possible.

Analysis and results

A detailed presentation about the methods used to analyse the data and the reasons for using those processes is provided, which includes a reflective commentary on the researcher's learning development in statistical processes where this adds value to the methods description. It is recognized that even though this is a doctoral level study, the level of statistical analysis that is used has had to be within the researcher's grasp both to properly execute and to understand outputs sufficiently to relate these to the research hypotheses. Invaluable in achieving these learning and research processing outcomes has been firstly a good understanding of intermediate-level statistical analysis, a degree of familiarity with the statistical analysis software application, SPSS, where much credit is also given to the accompanying suite of SPSS statistical analysis tutorials provided by Laerd Statistics online, which it is felt has both consolidated the researcher's existing competencies in statistical processes as well as providing a valuable self-teach resource to guide the understanding and application of new analysis tools and procedures.

Recall that the aim of the enquiry is to determine whether statistically significant differences exist between the levels of Academic Behavioural Confidence (ABC) of the three, principal research subgroups. The key, statistical outputs that have been used to establish this are the T-test for differences between independent sample means together with Hedges' 'g' effect size measures of difference. These are important outputs that can permit a broad conclusion to be drawn about significant differences in Academic Behavioural Confidence between the research subgroups, however a deeper exploration using Principal Component Analysis (factor analysis) has also been conducted on not only the results from data collected using the Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale but also of the Dyslexia Index metric which has enabled a matrix of T-test outcomes and effect sizes to be constructed. This has been a useful mechanism for untangling the complex interrelationships between the factors of academic behavioural confidence and the factors of dyslexia (as determined through the Profiler), and has contributed towards trying to understand which dimensions of dyslexia in students at university appear to have the most significant impact on their academic confidence in their studies.

[3673 / 63,074 (at 18 Jul 2018)]

Research Questions

Research Questions

- Do university students who know about their dyslexia present a significantly lower academic confidence than their non-dyslexic peers?

If so, can particular factors in their dyslexia be identified as those most likely to account for the differences in academic confidence and are these factors absent or less-significantly impacting in non-dyslexic students?

- Do university students with no formally identified dyslexia but who show evidence of a dyslexia-like learning and study profile present a significantly higher academic confidence than their dyslexia-identified peers?

If so, are the factors identified above in the profiles of dyslexic students absent or less-significantly impacting in students with dyslexia-like profiles?

How can these results be explained? Are the analysis outcomes sufficiently robust to suggest that identifying dyslexia in university student may be detrimental to their academic confidence? Further, that an identification of dyslexia may therefore be academically counterproductive?

Methodology

The research methodology for the enquiry is set out below as a workflow chronology as this serves to divide the reporting of how the research process has unfolded into ordered descriptions and justifications of the component parts of the project. In these, reference is made to pertinent methodology theory subsections where appropriate, and the extent to which, and reasons why this has been embraced or challenged. The workflow chronology is prefaced by a foreword which sets out the researcher's stance on the conventions of this part of a major, individual research enquiry which serves to underpin the chronology subsequently reported.

Stance - a perspective on the natire of social science

Stance - a perspective on the natire of social science

Science concerns finding out more about the nature of the natural and social world through systematic methodology based on empirical evidence (Science Council, 2017). Social science does not appear to be as objective as 'regular' science. 'Social' can be taken to mean as relating to human society and all of us in it and by its very nature is complex, multifactorial and sometimes convoluted. Observing and attempting to explain the activities of the world's peoples and the diversity of their functioning within it is surely the evidence. The methodology of social science research arguably attempts to unravel the ethnography of human attitudes, behaviour and interrelationships in ways which might however, isolate behavioural, attitudinal or societal variables from their interrelated co-variables. This happens as a result of devising methods and processes to observe and analyse behaviours or attitudes and subsequently attempt to explain results that may be difficult to interpret and gain meaning from so as to formulate conclusions with a degree of conviction or certainty. It seems clear to this researcher at least, that most research studies in the Social Sciences, of which education research may be considered one branch, are incremental in nature, generally conservative in the research approach adopted and more often than not produce research outputs that may as much conflate knowledge as advance it. This seems to be particularly the case in research about educational and learning differences which are identified as atypical in comparison with supposedly normal learning characteristics, styles and attributes.

The overview in the Theoretical Perspectives section has summarized Bandura's strong argument in his Social Cognition Theory, decades in development, that people should be viewed as self-organizing, proactive, self-reflective and self-regulating and not merely reactive organisms shaped by environmental forces or inner impulses. Law (2004) strongly argues that the methods that are devised to explore complexities such as these do more than merely describe them because these methods are contingent on the research 'trend' at the time and may as much influence and create the social realities that are being observed as measure them. This is because the conventionality of the 'research methods' processes that we are taught, supposedly fully considered and perfected after a century of social science 'tend to work on the assumption that the world is properly to be understood as a set of fairly specific, determinate and more or less identifiable processes' (ibid, p5). But the alternative (i.e. Law's) viewpoint is to challenge this global assumption on the basis that the diversity of social behaviours, interactions and realities is (currently) too complex for us to properly know (= the epistemological discourse), and hence argues that consequently, the shape of the research should accommodate the kind of fluidity in its methodology that is responsive to the flux and unpredictable outcomes of the mixtures of components and elements that are the focus of the enquiry. If this mindset is adopted, then in follows - so the argument goes - that the research output might be all that more convincing. Taking this approach to devising and actioning a research methodology seems analogous to Kelly's view of the societies of peoples whereby individuals integrate with their societies as scientists [sic] and the mechanisms through which this is accomplished is by constructing representational models of their world realities so that they can navigate courses of behaviour in relation to it (Kelly, 1955).

This introduction to the Research Methodology thus sets out the researcher's standpoint on the constraints of prescriptive research processes because to follow them verbatim especially creates a tension between such an obedient mindset and the context within which this enquiry is placed and shaped - that is, one that challenges conventional analyses of learning difference and strives to locate it along a spectrum of diversity which equally challenges the traditional acceptance of neurotypical as 'normal' (Cooper, 2006) and everything else as an aberration. This means that although at the outset a fairly clear sense of what needed to be discovered as the product of the enquiry was constructed, elements of grounded theory as a research methodology have been part of the research journey which at times it must be admitted, has drifted a little towards reflecting on the aetiologies of both dyslexia and academic confidence rather than merely reporting them. But it has also been important to regularly re-document these reflections on both product and process which, despite a tentative acceptance of the Popkewitzian argument that research is more than the dispassionate application of processes and instruments because it needs to embrace the underlying values and shared meanings of the research community within which it is located (Popkewitz, 1984), in the field of dyslexia research, consensus about the nature and origins of the syndrome remains as yet an objective rather than a reality - as outlined at the top of this paper - an irony that flies in the face of, for example, Rotter's strongly argued proposition that the heuristic value of a construct is [at least] partially dependent on the precision of its definition (1990, p489).

Thus despite the indistinctness of shape and character that surrounds the dyslexia syndrome, the research design has tried hard to retain focus on the primary objective which has been to evidence that students with unidentified dyslexia-like profiles have a stronger sense of academic confidence than identified dyslexic students, and has attempted to develop an enquiry that traces a clear path through the somewhat contentious fog that is dyslexia research.

Workflow chronology

Workflow chronology

Key steps in the workflow chronology are marked by learning and research process landmarks that have determined the final architecture of the project. This workflow chronology identifies and documents how these have influenced this enquiry and aims to present firstly how the researcher's interest in the impact of dyslexia on learning at university was kindled by learning practitioner experience, and as the project has progressed, how key realizations based on a better understanding of theory and careful reflection on how it has reshaped thinking migrated the research agenda onto a slightly different track:

- The preceding small-scale enquiry:

The legacy of outcomes from the researcher's preceding Masters' dissertation (Dykes, 2008) has had a significant impact on the development of this current project. As a preceding study, that small-scale enquiry within the dyslexic student community at a UK university was interested in understanding why some students with dyslexia were strong advocates of the learning support value provided by a dedicated learning technology suite staffed by dyslexia and disability specialists as evidenced through such students making frequent use of the suite and services throughout their time at university. Whereas at the same time, others with apparently similar dyslexic profiles appeared to be of the opposite disposition as these students rarely visited the technology suite or contacted the staff despite initially registering for access to the resources and services. It was thought that this disparity might, in part at least, be due to differences in the attitudes and feelings of students with dyslexia to their own dyslexia but particularly their perceptions about how it impacted on their access to, and their engagement with their learning at university. The study attempted to reveal these differences through exploration of (academic) locus of control as a determining variable by discriminating research participants into 'internalizers' or 'externalizers' as informed by the theories and evaluative processes widely acreditted to Rotter (1966, 1990). The hypothesis being considered was that students who did not use the learning technology suite and support services were likely to be internalizers whilst those who were regular 'customers' and frequently requested learning support from the staff, likely to be externalizers. This was formulated out of an extrapolation of the literature reviewed which suggested that externalizers were likely to be significantly more reliant on learning support services to help with and guide their studies in comparison to internalizers, who typically presented the more independent learning approaches generally observed amongst the wider student community. It was expected that this would be related to their attitudes and feelings about their dyslexia. As a member of staff of the suite at the time, privileged access to computer workstation log-in credentials was granted for the purposes of the research and this was used to determine which dyslexic students were frequent users of the service and which were not. Through a process of eliminating conflating variables, the research-participant base was established which eventually provided a sample size n=41 of which 26 were regular student users of the service and 15 were not. Data was collected through a self-report questionnaire which asked participants to rate their acquiescence using Likert-style responders to a selection of statements about learning and study preferences and about their feelings towards their dyslexia.

By deconstructing academic locus of control into factors and structuring the questionnaire statements accordingly, some small but significant differences between student profiles did emerge after the data was analysed although overall, the results were inconclusive. However a valuable output of the study was the development of what were termed at the time, Locus of Control Profiles. An example of the profiles generated from three respondents' data is shown (right). These were diagrams that represented the numerical conversion of each participant's responses to elements of the data collection questionnaire that were then aggregated into 5 distinct factors that the literature had shown were often associated with locus of control. These factors were attempting to measure respectively: Affective Processes (AP), Anxiety regulation and Motivation (ARM), Self-Efficacy (SEff), Self-Esteem (SEst), and Learned Helplessness (LH) and each axis of the profile diagrams represented each of these factors. Due to the methods used to code the data collected from this section of the questionnaire, the magnitude of the area of the polygons generated in these profile diagrams represented the degree of internal locus of control presented by each participant. Greater areas represented higher levels of internal locus of control. Hence it was possible to differentiate internalizers from externalizers given boundary values which, it must be admitted now, were somewhat arbitrarily determined, but which nevertheless worked at the time and enabled an analysis process of sorts to be completed.

By deconstructing academic locus of control into factors and structuring the questionnaire statements accordingly, some small but significant differences between student profiles did emerge after the data was analysed although overall, the results were inconclusive. However a valuable output of the study was the development of what were termed at the time, Locus of Control Profiles. An example of the profiles generated from three respondents' data is shown (right). These were diagrams that represented the numerical conversion of each participant's responses to elements of the data collection questionnaire that were then aggregated into 5 distinct factors that the literature had shown were often associated with locus of control. These factors were attempting to measure respectively: Affective Processes (AP), Anxiety regulation and Motivation (ARM), Self-Efficacy (SEff), Self-Esteem (SEst), and Learned Helplessness (LH) and each axis of the profile diagrams represented each of these factors. Due to the methods used to code the data collected from this section of the questionnaire, the magnitude of the area of the polygons generated in these profile diagrams represented the degree of internal locus of control presented by each participant. Greater areas represented higher levels of internal locus of control. Hence it was possible to differentiate internalizers from externalizers given boundary values which, it must be admitted now, were somewhat arbitrarily determined, but which nevertheless worked at the time and enabled an analysis process of sorts to be completed.

The factors emerged out of the literature review of the enquiry which had referred to many studies where levels of these constructs in learners with dyslexia were observed to have been siginificantly different than typically seen in non-dyslexic individuals (eg: Kerr, 2001, Burden & Burdett, 2005, Humphrey & Mullins, 2002, Riddick et al, 1999, Burns, 2000, Risdale, 2005). The literature also appeared to be showing that dyslexic individuals were more likely to be externalizers than internalizers in this locus of control context (eg: Bosworth & Murray, 1983, Rogers & Saklofske, 1985) because these individuals perceived, accurately or not, that their dyslexia would naturally put them at a learning disadvantage, not least due to their perception of their dyslexia as a learning disability rather than a learning difference in contemporary learning environments. Hence it was argued that these students would be expected to need additional support and resources in order to engage with their curricula on a more equal footing to their non-dyslexic peers. Originally the profiles were devised as a means to visually interpret and find meaning in the complex data that the enquiry had collected. No other studies had been found that presented multi-factoral outputs in a similar way and so in this respect, this representation of results in this way was highly innovative. On reviewing these individual participant-response profiles collectively, it was clear that they could be sifted into groups determined as much by striking similarities as by clear contrasts between them. The limitations of the enquiry recognized that there was much more information contained in these profile diagrams and their groupings than could be analysed and reported at the time and that these could be part of a further research project. It was also identified that a greater understanding of the relationships between the 5 factor constructs and locus of control and how these related to dyslexia in comparison to learners with no dyslexia was a necessary prerequisite for further work. It was also documented that an equally greater appreciation of 'due scientific process' would also be required for a later project especially in statistical analysis processes for example, gaining an understanding of what is now known to the researcher as principal component analysis. Despite this, it was recognized that the data generated through the self-report questionnaire were non-parametric, indeed with Likert-style attitudinal statements presented to participants with just two anchor-point choices - 'I generally agree with ...' or 'I generally disagree with...', the gradation of the data collected was extremely coarse. Clearer planning for the questionnaire design may have led to finer anchor-point gradings which would have facilitated a more cogent statistical argument to support the enquiry outcomes. Nonetheless, when this data was coded so that statistical analysis was possible, the non-parametric nature of the data collected was recognized, leading to use of the Mann-Whitney U and Kolgorov-Smirnoff Z tests to expose any significant differences between medians. It is of no surprise therefore, especially with hindsight and with the researcher's more recently acquired statistical competencies, that the outcomes of the analysis were inconclusive. But the project did uncover interesting realities about the feelings and attitudes of students with dyslexia to their learning at university and worth reporting amongst these were statistically significant differences between the attitudes of 'internalizers' and 'externalizers' to their perceptions of the intensity of study required to match the academic performance of their non-dyslexic peers, and also about their feelings about the university's provision for the perceived uniqueness-of-need of students with dyslexia, an observation that is consistent with the argument that by accepting the principles of Universal Design for Learning, as previously outline, this 'uniqueness' would be better served. Also of significant value were the sometimes quite heartfelt disclosures of frustration, embarrassment and feelings of being misunderstood expressed by many of the respondents, and also in relation to conforming to institutional expectations, even pressure, to engage with support structures outwardly designed to ameliorate study difficulties and challenges - well-meaning as these are, but which actually increased were reported study burdens rather then reduce them, especially in relation to time management. For example:- "I did not use dyslexia support at all last year ... [I] find the extra time in having to organize dyslexia support well in advance is not helpful as I would much prefer to ask for help as and when I have a problem" [respondent #28, Dykes, 2008, p85]

- "I am unable to use study support sessions as I am already finding it hard to keep up with the course and don't have time" [respondent #34, ibid, p88]

- "Going for help with studies takes up more of my time when i'm already struggaling with too much work and not enough time and it rarely helps as I can't explain why I'm struggaling, otherwise I would have just done it in the first place ... [and] all the forms assosated with getting help or reimbursement for books etc means that I keep putting [it] off - forms are something I am daunted by" [respondent #20, ibid, p98]

Thus is has been that enquiry background that has fuelled this current study notably through three, lasting impression of this earlier small-scale enquiry which emerged. The first was that in this higher education context at least, it seemed that as many students with identified dyslexia appeared to be at ease with the challenges of their studies as were those who were burdened with them and struggled (Dykes, 2008). This was in part demonstrated by a clear distinction between students who appeared ambivalent towards the additional support provisions that they had won through their Disabled Students' Allowance, sometimes citing these as not really necessary and evidenced in part by a significant lack of interest in taking advantage of training opportunities for the assistive technologies that they had been provided with to make studying easier for them, and those who took quite the opposite standpoint. A similar result has been reported in another study where more than half of the 485 university students with dyslexia that were surveyed indicated that they had not taken up the assistive technology training that they had been offered although the reasons for this were not explored in detail with no distinction being made between training on hardware and training on software or assistive technology applications (Draffen et al, 2007). A later study amongst disabled students at the same institution (which coincidentally was also my own university both as a student and a member of staff) also uncovered a significant proportion of participants in the research cohort not taking up these training opportunities, citing time constraints, the burdensome nature of training regimes or the lack of contextual relevance to their studies as some of the reasons (Seale et al, 2010). Clearly this finding is a corroboration of the student comments reported above. A significant and possibly related factor may also be expressions of feelings of guilt about being given expensive hardware such as laptops and other devices that some dyslexic students felt they should not be entitled to because they did not consider themselves to be learning disabled and hence expressed unease this additional support that they did not feel that they really needed might be giving them an unfair advantage over their peers (Dykes, 2008).

The second feature that emerged from the earlier study which has impacted on the research methodology of this current project was evidence of a significant variability in attitudes towards their own dyslexia expressed by students in the earlier survey which appeared to be as much related to wide range of dyslexia 'symptoms' presented and students' perceptions of the relevance of these to their studies, as to other psychological factors such as self-esteem, academic self-efficacy and learned helplessness, collectively reflecting either a generally positive or negative approach towards the challenges of study at university - hence the interest in relating these factors to the degree of internal or external locus of control. The ways in which this has influenced the current research process has firstly been to flag up the complexity of the dyslexia syndrome and hence how challenges in clearly establishing what dyslexia means at university conflate many dyslexia research paradigms; and secondly how complex, psycho-educational factors that affect every individual's learning behaviours and attitudes to their studies can be teased out into identifiable variables or dimensions that can be somehow measured and thus are comparable across research subgroups.

The third factor that has influenced and strongly motivated this current project has been the significant proportion of student respondents in the earlier study who strongly expressed their feelings that their dyslexia was about much more than writing challenges and poor spelling, and also how being differentiated from other learners as a result of their dyslexia being identified to them had impacted negatively and had lasting effects.

- "Dyslexia is seen too much as a reading and writing disorder ... I am just not hard wired in [the same] way [as others]. I just end up feeling stupid 'cos I just don't get it" [respondent #12, Dykes, 2008, p95]

- "I find searching databases and getting started on writing especially difficult" [respondent #34, ibid, p88]

- "I avoid using computers at university as they are not set up the same as mine at home and I find it confusing" [respondent #19, ibid, p109]

- "My spelling and reading sometimes gets worse when I think about dyslexia. I get annoyed with the tact that people can blame bad spelling on dyslexia" [respondent #11, ibid, p82]

- "I am not sure dyslexia is real because I believe everyone, if given the chance to prove it, could be a bit dyslexic. So perhaps my problem is that I am not as intelligent as others, or that my lack of confidence from an early age decreased my mental capability" [respondent #9, ibid, p94]

- "In my academic studies I have always had good grades but never found it easy to concentrate on my work" [respondent #27, ibid, p100]

- "... I will be thinking of one word but write a completely different word, for example I will be thinking 'force' but write 'power' ... I'm obviously cross-wired somewhere" [respondent #33, p101]

- "When I do not understand, most people think the written word is the problem but [for me] it is the thought process that is different" [respondent #41, ibid, p128]

- "I was separated all the time [in primary school] and made out to be different. I feel this wasn't the best way to deal with me" [respondent #39, ibid, p103]

Hence taking the perspective that dyslexia can be a multifactoral learning difference that is much more than a manifestation of a reading and spelling disorder shaped by phonological deficits accumulated during early years has driven the desire to develop an alternative process for exploring such factors or dimensions in adult learners, thus forming the rationale for innovating the Dyslexia Index Profiler used in this project. - Defining dyslexia: the professional practitioners' view:

An outcome of the early stages of the literature review on dyslexia in this current project was an emerging unease about the lack of consensus amongst researchers, theorists and practitioners about how dyslexia should be defined. Having little recourse to a consensual definition about dyslexia was felt to be an obstacle in the research design, not least as it was clear that researchers and theorists tended to underpin their reports with exactly that: a definition of dyslexia. It was felt that to conduct a research study about dyslexia in the absence of a universally agreed definition of what it is could be problematic and it was recognized that others had expressed a similar disquiet, in some cases constructing alternative theories to resolve the issue of definition discrepancies (eg: Frith, 1999, 2002, Evans, 2003, Cooper, 2006, Armstrong, 2015). Some of these have been referred to above but in summary, what seemed to be emerging from the continued debate was that first of all, adherents to the deficit definitions which have traditionally been the preserve of clinicians who diagnose dyslexia have been numerous amongst earlier research and hence, this polarizes the research outcomes into alignment or not with this definition perspective. Secondly, the social constructivist model has encouraged the egress of 'differently-abled' as a definition standpoint which has gained in research popularity not least driven by inclusion agendas. Lastly, an increasing research narrative is supporting the argument that defining dyslexia is elusive to the extent that the label is unhelpful and laden with such stigma as to be academically counter-productive.

These issues have been discussed earlier however a practical outcome of this concern was an interest in exploring how dyslexia is framed in professional practice. The led to the development and subsequent deployment of a small-scale sub-enquiry, in fact more of a 'straw poll' given its limited methodological underpinnings, that aimed to construct a backdrop of contemporary viewpoints from amongst dyslexia support practitioners about how dyslexia is defined in their communities of practice. There are precedents for an enquiry that tries to explore professionals' knowledge about dyslexia. Bell et al (2011) conducted a comparative study amongst teachers and teaching assistants in England and in Ireland who had professional working contact with students with dyslexia to explore how teachers conceptualize dyslexia. The research asked teachers and teaching assistants to describe dyslexia as they understood it and the data collected was categorized according to Morton & Frith's causal modelling framework that defines dyslexia as either a behavioural condition, a cognitive one or of biological origin (Morton & Frith, 1995). Their paper highlighted concerns that the discrepancy model of dyslexia - that is, where the difficulties are assumed to be intrinsic to the learner - persisted amongst practitioners, where discrepancy criteria were more frequently used to identify learners with dyslexia rather any other category or criterion (ibid, p185). Significant in Bell's study was an acknowledgement of the wide-ranging spectrum of characteristics associated with dyslexia and learning and hence, the importance of developing highly individualized teacher-learner collaborations if students with learning differences are to be fairly accommodated in their learning environments. Emerging from this was the call for better teacher-training and development that enabled professional educators to gain a greater understanding of the theoretical frameworks and most up-to-date research surrounding dyslexia and how it can be both identified, formally or otherwise, and subsequently embraced in learning curricula. Soriano-Ferrer & Echegaray-Bengoa (2014) attempted to create and validate a scale to measure the knowledge and beliefs of university teachers in Spain about developmental dyslexia. Their study compiled 36 statements about dyslexia such as 'dyslexia is the result of a neurological disorder', 'dyslexic children often have emotional and social disabilities', 'people with dyslexia have below average intelligence' and 'all poor readers have dyslexia'. Respondents were asked to state whether they considered each statement about dyslexia to be true, false or that they did not know. Unfortunately their paper made no mention of the resulting distribution of beliefs, merely claiming strong internal consistency reliability for their scale. A similar, earlier (and somewhat more robust) study also sought to create a scale to measure beliefs about dyslexia with the aim of informing recommendations for better preparing educators for helping dyslexic students (Wadlington & Wadlington, 2005). The outcome was a 'Dyslexia Belief Index' which indicated that the larger proportion of research participants, who were all training to be or already were education professionals (n=250), held significant misconceptions about dyslexia. Similar later work by Washburn et al (2011) sought to gauge elementary school teachers' knowledge about dyslexia, using a criteria that claimed that 20% of the US population presents one or more characteristics of dyslexia. Other studies which also used definitions of dyslexia or lists of characteristics of dyslexia were interested in attitudes towards dyslexia rather than beliefs about what dyslexia is (eg: Honrstra et al, 2010, Tsovili, 2004).

Thus it was felt appropriate to echo Bell's (op cit) interest and attempt to determine the current viewpoint of professional practitioners at university by exploring their alliances with the some of the various definitions of dyslexia. 'Professional practitioners' are taken as academic guides, learning development tutors, dyslexia support tutors, study skills advisers and disability needs assessors but the enquiry was scoped broadly enough to include others who work across university communities or more widely with dyslexic learners. Given that the definition of dyslexia may be considered as 'work in progress' it is not unreasonable to suppose that an academic researcher may use one variant of the working definition of dyslexia in comparison to that applied by a disability needs assessor or a primary school teacher for instance. Hence it was felt that finding out the extent to which dyslexia is framed according to the domain of functioning of the practitioner would provide a useful, additional dimension to this project's attempt to understand what dyslexia is.

The enquiry was built around 10 definitions of dyslexia which were sourced to try to embrace a variety of perspectives on the syndrome. These were built into a short electronic questionnaire and deployed on this project's webpages (available here). The questionnaire listed the 10 definitions in a random order and respondents were requested to re-order them into a new list that reflected their view of them from the 'most' to 'least' appropriate in their contemporary context. The sources of the 10 definitions were not identified to the participants during completion of the questionnaire because it was felt that knowing who said what may introduce a bias to answers. For example, it was felt that a respondent may align their first choice with the definition attributed to the British Dyslexia Association (which was one of the sources) more out of professional/political correctness than according to their genuine view. Conversely, a respondent may dismiss the definition attributed to a TV documentary as inappropriate because this may be perceived as an unscientific or potentially biased source. On submission of the questionnaire the sources of all of the definitions were revealed and participants were told in the preamble to the questionnaire that this would occur. If was felt that curiosity about sources may be a contributory motivating factor to participate. Also provided in the questionnaire was a free-text area where respondents were able to provide their own definition of dyslexia if they chose to, or add any other comments or views about how dyslexia is defined. Additionally, participants were asked to declare the professional role and practitioner domain - for example 'my role is: 'a university lecturer in SpLD or a related field' '. The questionnaire was only available online and was constructed using features of the newly available HTML5 web-authoring protocols which enabled an innovative 'drag-drop-sort' feature. The core section that comprises the definitions and demonstrates the list-sorting functionality is below.

It was distributed across dyslexia forums, discussion lists and boards. and was also promoted to organizations with interest in dyslexia across the world, who were invited to support this straw poll enquiry by deploying it across their own forums or blogs or directly to their associations' member lists. Although only 26 replies were received, these did include a very broad cross-section of interests ranging from disability assessors in HE to an optometrist. Although a broad range of definitions was sought it is notable that 8 out of the 10 statements used imply deficit by grounding their definitions in 'difficulty/difficulties' or 'disorder', which is a reflection of the prior and prevailing reliance on this framework. With hindsight, a more balanced list of definitions should have been used, particularly including those pertinent to the latest research thinking which at the time of the questionnaire's construction had not been fully explored.

Outcomes:- The relatively positive definition #5, that of the British Dyslexia Association, which recognizes dyslexia as a blend of abilities and difficulties hence marking a balance between a pragmatic identification of the real challenges faced by dyslexic learners and a positive acknowledgement of many of the positive, creative and innovative characteristics frequently apparent in the dyslexic profile, was selected and placed in first, second or third place by 16 respondents with 12 of those placing it first or second. This only narrowly beat definition #8, noting dyslexia principally as a ‘processing difference’ (Reid, 2003) which was placed in first, second or third place by 14 respondents, also with 12 of those placing it in first or second place. Interestingly, this definition #8 beat the BDA’s definition for first place by 6 respondents to 5. The only other definition being selected and placed first by 6 respondents was definition #9 which characterizes dyslexia (quite negatively) with a ‘disability’ label, this being the only definition to include this in its wording indicating its origination in the USA where the term ‘learning disability’ is more freely used to describe dyslexia.

- Of the three results received from university lecturers in SpLD, two placed the BDA’s definition of a ‘combination of abilities and difficulties…’ in first position with the third respondent choosing just the definition describing dyslexia as a specific learning disability.

- 7 respondents described their professional roles as either disability/dyslexia advisors or assessors by which it is assumed these are generally non-teaching/tutoring roles although one respondent indicated a dual role in being a primary teacher as well as an assessor. None of these respondents used the BDA’s definition as their first choice, with two not selecting it at all. Of the remaining five, this definition was either their second or third choice. Two of these respondents put definition #8, ‘a processing difference…’ in first place with three others choosing definition 9, ‘a specific learning disability’ to head their list. Perhaps this is as we might expect from professionals who are trying to establish whether an individual is dyslexic or not because they have to make this judgment based on ‘indications’ derived from screenings and tests which are comprised of intellectual and processing challenges particularly designed to cause difficulty for the dyslexic thinker. This is central to their identifying processes. Although the professionalism and good intentions of assessors and advisors is beyond doubt, it might be observed that there is perhaps a 'culture of diagnosis’ which predominantly marks the dyslexia identification process and that this may generate an unintended but nevertheless somewhat dispassionate and detached familiarity with the association of 'diagnosis' with clinical evaluations of something wrong, and hence be not fully appreciative of the impact that learning about their dyslexia might have on an individual who, most likely given a learning history peppered with frustration, difficulties and challenges, has now experienced an ‘assessment’ that, in the interests of ‘diagnosis’, has, yet again, spotlighted those difficulties and challenges. To be fair, some studies have reported that some individuals who find out about their dyslexia have been recorded as remarking that is was a liberating process rather than a negative one (eg: Riddick 2000, Morgan & Klein, 2000, Kong, 2012).

- One respondent was an optometrist ‘with a special interest in dyslexia’ who selected just one definition in their list, this being #9, ‘a specific learning disability…’ but additionally provided a very interesting and lengthy commentary which advocated visual differences as the most significant cause of literacy difficulties. An extensive, self-researched argument was presented, based on an exploration of ‘visual persistence’ and ‘visual refresh rates’. The claimed results showed that ‘people who are good at systems thinking and are systems aware are slow, inaccurate readers but are good at tracking 3D movement, and vice versa’, adding that ‘neurological wiring that creates good systems awareness [is linked with] slow visual refresh rates and that this results in buffer overwrite problems which can disrupt the sequence of perceived letters and that can result in confusion in building letter to sound associations’. This respondent was also of the opinion that none of the definitions offered were adequate (actual words used not repeatable here) with some particularly inadequate, commenting further that ‘I do not know what it would mean to prioritize a set of wrong definitions’ - a point which distils much of the argument presented in my thesis so far relating to issues of definition impacting on research agendas.

So from this relatively cursory inspection of the key aspects of respondents’ listings overall, it seems fairly evident that a clear majority of respondents align their views about the nature of dyslexia with both the that of the British Dyslexia Association and with that of an experienced practitioner, researcher and writer Gavin Reid, (2003), whose work is frequently cited and is known to guide much teaching and training of dyslexia ‘support’ professionals. With the exception of Cooper’s description of dyslexia being an example of neuro-diversity rather than a disability, difficulty or even difference, definitions used by researchers and even professional associations by and large remain fixed on the issues, challenges and difficulties that dyslexia presents when engaging with the learning that is delivered through conventional curriculum processes. This approach compounds, or certainly tacitly compounds the ‘adjustment’ agenda which is focused on the learner rather than the learning environment. Although it is acknowledged that more forward-looking learning providers are at least attempting to be inclusive by encouraging existing learning resources and materials to be presented in more ‘accessible’ ways – at least a pragmatic approach – this remains some distance away from adopting the principles of Universal Design for Learning and operationalizing them in university teaching contexts. - Existing dyslexia evaluators and identification processes in higher education - why these were dismissed:

The majority of current devices used in higher education settings for identifying dyslexia in students search diagnostically for deficits in specific, cognitive capabilities and use baseline norms as comparators. These are predominantly grounded in lexical competencies. As long as the literacy-based hegemony prevails as the defining discourse in judgments of academic abilities (Collinson & Penketh, 2010) there remains only a perfunctory interest in devising alternative forms of appraisal that might take a more wide-ranging approach to the gauging of academic competencies and especially how these may be impacted by learning differences. All of the tools use a range of assessments which are built on the assumption that dyslexia is principally a phonological processing deficit that is accompanied by other impairments in cognitive functioning which collectively, are said to disable learning processes to a sufficient extent that the 'diagnosed' individual is left at a substantial disadvantage in relation to their intellectually-comparable peers. The principle reason for identifying a student as dyslexic in university settings - well-meaning as this is - has been to evidence entitlement to learning support funding through the Disabled Students' Allowance (DSA) within which dyslexia has been regarded as a disability. In the light of persistent funding constraints, a UK Government review of the provision of the DSA, first published in 2014, originally proposed the removal of dyslexia, termed Specific Learning Difficulties, from the list of eligible impairments, mental health conditions and learning difficulties, but to date the proposals set out in the review have not been actioned, not least as a result of strong lobbying from organizations such as the British Dyslexia Association, PATOSS (the Professional Association for Teachers and Assessors of Students with Specific Learning Difficulties) and ADSHE (the Association of Dyslexia Specialists in Higher Education). Although undergoing a less intrusive screening process is usually the first stage in attempting to establish whether a student presents dyslexia or not, full assessments can only be conducted by educational psychologists and although the battery of tests and assessments administered might be considered as necessarily comprehensive and wide-ranging, due in no small part to the requirement to ensure that any support funding stream allocated results from an accountable process, undergoing such cognitive scrutiny is time-consuming, fatiguing for the student being 'diagnosed' and can add to feelings of difference (Cameron, 2015), anxiety (eg: Carroll & Iles, 2006, Stampoltzis, 2017) and negative self-worth (Tanner, 2009) typically experienced by learners who may already be trying to understand why they find academic study so challenging in comparison to many of their peers.