| w | statement | H / L | r | RC ? |

| 0.80 | When I was learning to read at school, I often felt I was slower than others in my class | H | 0.51 | - |

| 0.53 | My spelling is generally very good | L | - 0.52 | RC |

| 0.70 | I find it very challenging to manage my time efficiently | H | 0.13 | - |

| 0.71 | I can explain things to people much more easily verbally than in my writing | H | 0.60 | - |

| 0.57 | I think I am a highly organized learner | L | - 0.08 | - |

| 0.48 | In my writing I frequently use the wrong word for my intended meaning | H | 0.67 | - |

| 0.36 | I generally remember appointments and arrive on time | L | 0.15 | - |

| 0.75 | When I'm reading, I sometimes read the same line again or miss out a line altogether | H | 0.41 | - |

| 0.76 | I have difficulty putting my writing ideas into a sensible order | H | 0.51 | - |

| 0.80 | In my writing at school, I often mixed up similar letters like 'b' and 'd' or 'p' and 'q' | H | 0.61 | - |

| 0.57 | When I'm planning my work I use diagrams or mindmaps rather than lists or bullet points | neutral | 0.49 | - |

| 0.75 | I'm hopeless at remembering things like telephone numbers | H | 0.41 | - |

| 0.52 | I find following directions to get to places quite straightforward | L | -0.04 | - |

| 0.57 | I prefer looking at the 'big picture' rather than focusing on the details | neutral | 0.21 | - |

| 0.63 | My friends say I often think in unusual or creative ways to solve problems | H | 0.20 | - |

| 0.52 | I find it really challenging to make sense of a list of instructions | H | 0.49 | - |

| 0.52 | I get my 'lefts' and 'rights' easily mixed up | H | 0.39 | - |

| 0.70 | My tutors often tell me that my essays or assignments are confusing to read | H | 0.36 | - |

| 0.64 | I get in a muddle when I'm searching for learning resources or information | H | 0.57 | - |

| 0.72 | I get really anxious if I'm asked to read 'out loud' | H | 0.36 | - |

discourse study-blog | resources | lit review maps | profiles

enquiry dysdefs QNR | dysdims QNR | research QNR

1st draft (Winter 2017/18)

1st draft (Winter 2017/18)

- ABSTRACT

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PROJECT OVERVIEW

- RESEARCH QUESTIONS

- STANCE

- RESEARCH IMPORTANCE

-

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

-

DYSLEXIA

DYSLEXIA

- A complex phenomenon or a psuedo-science?

- Dyslexia: the definition issues

- Dyslexia as a multifactoral difference

- Disability, deficity, difficulty, difference or none of these?

- Labels, categories, dilemmas of difference, inclusivity

- Impact of the process of identification

- To Identify or Not To Identify? - that is the question

- Measuring dyslexia - "how dyslexic am I?"

-

ACADEMIC CONFIDENCE - theoretical foundations of the construct

ACADEMIC CONFIDENCE - theoretical foundations of the construct

-

ACADEMIC SELF-EFFICACY

ACADEMIC SELF-EFFICACY

- The construct of academic self-efficacy

- The relationships between academic self-efficacy and academic achievement

- Confidence as a learning attribute

- The location of academic confidence within the construct of academic self-efficacy

- Measuring academic confidence: the Academic Confidence Scale

- Academic Behavoural Confidence

- Historical Development of the ABC Scale

- Recent research using the ABC Scale

- Connecting ABC to academic achievement

- Use of the ABC scale in this research project

-

-

RESEARCH DESIGN

RESEARCH DESIGN

-

RESULTS and ANALYSIS

RESULTS and ANALYSIS

-

DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

- LIMITATIONS

- CONCLUSIONS

- DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

- REFERENCES

-

APPENDICES

APPENDICES

Abstract

Abstract

This project is interested in the impact of the dyslexic label on university students' sense of academic confidence.

The premise being tested is that students with an identified dyslexic learning difference present a lower academic confidence than not only their non-dyslexic peers but, more significantly, than their non-identified, apparently dyslexic peers. Confidence in an academic context has been identified as a significant contributor to academic achievement not least due to academic confidence being considered as a sub-construct of academic self-efficacy which has been widely researched. Exploring how academic confidence is affected by learning differences widely attributed to dyslexia is thought to be a fresh approach to exploring how many students tackle their studies at university. The metric used to gauge academic confidence has been the Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale, developed by Sander & Sanders (2006) and which is gaining ground amongst researchers as a useful tool for exploring the impact of study behaviours on academic outcomes.

As for dyslexia, current metrics used for assessing dyslexic learning differences are coarse-graded and tend to focus on diagnosing the syndrome as a disability in learning contexts. The principle objective in identifying dyslexia at university (in the UK) is to provide a means to access learning support funding. Whilst this may have advocates amongst those outwardly pursuing social justice in learning for example, evidence suggests that stigmatization associated with being labelled as 'different' can be academically counterproductive. This project sought to detach dyslexia from the learning disability agenda firstly because there remains a persistently unresolved debate about what dyslexia is, and secondly because the syndrome presents a range of strengths as well as difficulties in relation to learning engagement in literacy-based education systems. To this end, no current dyslexia assessment tools were felt to be appropriate for discriminating those with unidentified dyslexia-like learning profiles from both their dyslexia-identified peers and the wider student population at university. Hence, a fresh, Dyslexia Index Profiler has been developed which attempts to take a more neutral position as a study-preference evaluator that can provide indications of dyslexia-like learning characteristics, as opposed to adopting the difficulty/disability-loaded approach typically seen in other dyslexia assessment tools.

In this survey of 166 university students, the research outcomes indicate that the identification of learners as 'different' may substantially impact on academic confidence and that this may be a more significant factor than that attributed to the impediments and obstacles to effective learning at university that are claimed to be causally connected to the learning differences themselves. Analysis of the data has produced a moderate effect size of g = 0.48 between the Academic Behavioural Confidence of students with identified dyslexia and that of students with apparently unidentified dyslexia-like study profiles. The ABC of the dyslexic subgroup was lower. This result was supported by a statistically significant difference between the mean ABC values of the two groups (t = 1.743, p = 0.043)*.

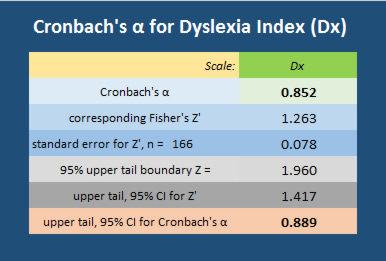

It is recognized that one limitation of the research has been the untested validity and external reliability of the Dyslexia Index Profiler. However the tool has served its design purpose for this study and this is indicated by good internal consistency reliability shown by a Cronbach's α coefficient of 0.852 (with an upper-tail, 95% confidence limit of α = 0.889)*. It is recommended that further research should be conducted to develop the Profiler, especially as this high value for α may be indicating some scale-item redundancy. Given this further work, a more robust, standardized tool might then be available to contribute to other studies and which might also show promise for a fresh approach to be taken towards identifying dyslexia and dyslexia-like study profiles across university communities where this might be considered appropriate. The Profiler could also become a valuable mechanism for enabling students to more fully understand their learning strengths and difficulties and hence how to integrate these into their study strategies to enhance their opportunities of realistally achieving the academic outcomes that they are expecting from their time at university.

The research is important because to date, no existing, peer-reviewed studies specifically investigating the relationships between academic confidence and dyslexia have been found. It is also important because the research outcomes may contribute to the debate about whether identifying so-called dyslexia amongst university-level learners makes a positive contribution to their ultimate academic outcomes or that the benefits apparently attributed to being labelled as dyslexic are outweighed by the stigma persistently associated with disability and difference, not only in learning environments but in society more generally.

[*to be checked again and verified before final submission}

[words this section: 714 / aggregated word count: 63,074 = 78% written (at 08 Jan 2018) ]

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

The researcher acknowledges with thanks, the study support and academic guidance provided by the research community at Middlesex University, the Research Degrees Administration Team at the Department of Education and in particular, the advice and interest of the supervisory team of Dr Victoria de Rijke and Dr Nicola Brunswick.

The researcher also expresses graditude to Middlesex University for the 3-year Research Studentship funding, without which, this research project would not have been possible

[74 / 63,074 (at 08 Jan 2018)]![]()

Overview

Overview

Dyslexia and Academic Confidence at University

Dyslexia is identified in many students as a learning difference but the syndrome remains widely debated (eg: Elliott & Grigorenko, 2014). Nonetheless, the impacts of dyslexia and dyslexia-like profiles on learning are readily apparent in literacy-based education systems ranging from initial identification in early-age learners who experience challenges in the acquisition of reading skills, to university students who attribute many of their struggles to adapt to the independent and self-managed learning processes that are core competencies in higher education learning to a dyslexia or dyslexia-like learning profile.

To gain a greater understanding of the issues is at least a first step towards meeting the learning needs of learning differences (Mortimore & Crozier, 2006), although encouraging the design and development of more accessible curricula - particularly in Higher Education - seems preferable to retrofitting the curriculum to the learner (Lancaster, 2008) by way of 'reasonable adjustments'. This might then mean that learners with dyslexia would feel more included and less 'different' (eg: Dykes, 2008, Thompson et al, 2015) or even that identifying their study profiles as falling within the dyslexia envelope is unnecessary, could be counterproductive in relation to positively advancing their academic achievement and may now be best considered as an alternative form of information processing (Tamboer et al, 2014) in teaching and learning environments that are sufficiently adaptable and flexible to accommodate difference without differentiation. When learning differences cease to impact on access to, and engagement with learning - in whatever ways this is ameliorated - it is reasonable to suppose that the persistent disability model of dyslexia, tacitly implied by 'diagnosis', 'reasonable adjustment' and 'support', will have reduced meaning. Instead, the positive strengths and qualities that form part of the dyslexia spectrum of apparent differences can be celebrated and integrated into the development of the learner in ways that will encourage a greater sense of academic agency to emerge, possibly reflected by stronger academic confidence which may contribute positively towards better and more successful academic outcomes at university (Nicholson et al, 2013).

This project is interested in learning more about how students with dyslexia or dyslexia-like profiles integrate their learning differences into their study-self-identity. It has explored their judgements of its impact on their study processes in relation to their sense of academic purpose, in particular the confidence expressed in meeting the academic challenges they face at university. A fresh, innovative profiler has been developed which attempts to offer an alternative understanding of learning difference which does not focus on deficit-discrepancy models and on disability. The research takes the standpoint that it may be students' awareness of their dyslexia and what the dyslexic label means to them that is the most significant factor impacting on their academic confidence when compared with the challenges that the dyslexia itself may present to their learning engagement. This is thought to be an innovative approach to dyslexia research and aims to challenge the persistent medical, deficit model of dyslexia and the labelling of the syndrome as a disability in Higher Education learning contexts where the prinicple aim is to enable access to differentiated learning support. The research is also expected to contribute to the discourse on the non- or late-reporting of dyslexia in university students (eg: Henderson, 2015), and also add to the limited range of research relating to the academic confidence of university students who are from minority groups, especially those deemed to have a learning disability in whatever ways this might be defined.

Hence the aim of this research project is to explore the relationship between the learning difference of dyslexia and specific aspects of academic agency at university. Zimmerman (1995) spoke of academic agency as 'a sense of [academic] purpose, this being a product of self-efficacy and academic confidence that is then the major influence on academic accomplishment' and it is through the principal concepts of academic self-efficacy and particularly academic confidence that this research project has been tackled. Exploring these relationships and how they are impacted upon by the learning difference of dyslexia is important because relationships revealed may contribute to the emerging discussion on the design of learning development and 'support' for groups of learners who feel marginalized or disenfranchised because conventional learning curriculum delivery tends to be out of alignment with their learning strengths, or due to their perceived stigma about being labelled as 'disabled' in a learning context. This project is particularly topical at this time in the light of plans for dyslexia to be disassociated from the (UK) Disabled Students' Allowance in the near future. Hence the research may contribute to an expected raised level of discourse about creating more inclusive curricula that supports a social justice agenda by arguing for a wider provision of undifferentiated learning development that is fully accessible and actively promoted to the complete, coherently integrated student community in HE and which moves away from the negatively-connatated perception of learning support as a remedial service both amongst academics and students at university (Laurs, 2010).

The key research focus has tested the hypothesis that, for a significant proportion of students with dyslexia, it is their awareness and feelings about how their dyslexia affects their studies at university that has a more significant impact on their academic confidence in relation to the learning differences that the apparent dyslexic condition itself may present. This is important to explore not only because attributes of academic agency and in particular, academic confidence, are increasingly widely reported as markers of future academic achievement but also because it further raises the issue of how to tackle the 'dilemma of difference' (Norwich 2010), originally identified as a significant factor in education by Minow (1985, 1990). This is especially pertinent as dyslexia has been shown to be negatively correlated with both academic confidence and academic achievement (eg: Barrett, 2005, Asquith, 2008, Sanders et al, 2009) indicating that significant interrelationships may be present.

[more content in preparation as required?]

[938 / 63,074 (at 08 Jan 2018)]

Research Questions

Research Questions

- Do university students who know about their dyslexia present a significantly lower academic confidence than their non-dyslexic peers?

If so, can particular factors in their dyslexia be identified as those most likely to account for the differences in academic confidence and are these factors absent or less-significantly impacting in non-dyslexic students?

- Do university students with no formally identified dyslexia but who show evidence of a dyslexia-like learning and study profile present a significantly higher academic confidence than their dyslexia-identified peers?

If so, are the factors identified above in the profiles of dyslexic students absent or less-significantly impacting in students with dyslexia-like profiles?

Is there a significant difference in academic confidence between non-dyslexic students and students with non-identified dyslexia-like profiles?

How can these results be explained?

[280 / 63,074 (at 08 Jan 2018)]![]()

Ethics and Permissions

Ethics and Permissions

This research study has been conducted in accordance with all the specified and regulatory protocols set out in the University Regulations of Middlesex University, London.

Following an application to the Ethics Subcommittee of the School of Health and Education, approval to pursue the research and report the results in the form of a thesis to be submitted to the university for consideration for the award of Doctor of Philosophy was obtained on 21st July 2015.

Informed consent was obtained from all research participants, whose confidentiaility and anonymity was protected, who were not harmed by and who participated voluntarily in this study, and were given the opportunity to withdraw the data they had provided from the research at any time.

This research study is independent and impartial, has not been influenced by any external source or agency and has been conducted in accordance with guidance provided in the ESRC Framework for Research Ethics (2015).

The researcher confirms that the research has been conducted with integrity and to ensure quality to the best of his ability and is entirely his own work.

[183 /63,074 (at 08 Jan 2018)]

Stance

Stance

In the domain of university education, my view, which is broadly based on over a decade's experience of trying hard to be a good academic guide, is that there is a burgeoning need to influence a change in the system of delivery - and most definitely assessment - of learning in Higher Education. As universities open their doors to a much broader spectrum of students through widening participation and alternative access schemes, I believe that many of these new faces, together with the more traditionally-seen ones, would benefit academically were there a better institutional-level understanding of the impact that individual differences have on educational engagement, ownership of learning (Conley & French, 2014) and hence, likely attainment.

The learning environments and processes that are generally prevalent at university are not informed by psychological knowledge and appear to be increasingly driven by the ‘student experience’ of university with the annual National Student Survey having a strong influence on what this is, as students are increasingly considered as consumers (Woodall et al, 2014). In the earlier period following its introduction in 2005, high ratings in the NSS had significant implications for funding, although the direct impact of the NSS on university budgets is now (2017) less significant because universities' income streams are largely from student fees. So whilst the direct financial influence of the NSS is reduced, this has been displaced by shift in emphasis towards how the outcomes of the survey bolster the reputations of universities, especially as viewed by the parents of the largest group of university 'customers', that is 18-24-year-olds. Through my experience in higher education during this last decade or so I have witnessed educational models based on communities of knowledge being displaced by ones that are more focused on the more attractive, social experiences of being at university. This may be more apparent in institutions that are less driven by research funding because these universities have to rely more unidimensionally on income sources generated from student fees to meet their costs: hence, more students equals greater income. Having worked in both WP (Widening Participation) and Russell Group universities, and networked with academic and learning development colleagues across the sector, this is my observation and although I concede that the underlying intention of the NSS is to positively influence teaching and learning quality and to make universities more accountable, the extent to which responding to 'the student voice' achieves this is the subject of continued research (eg: Brown et al, 2014) not least due to wide variations in how raw score data is interpreted (Lenton, 2015).

However, the 'knowledge model' is not without its failings either: arguably entrapped by a rigid pedagogy that in many cases remains rooted to a well-established didactic approach for transmitting knowledge, this kind of university learning can appear to be underpinned by the idea that it is sufficient to inculcate knowledge through a kind of passive, osmotic cognitive process. Notions of ‘student-centeredness’ and inclusivity are less important in this ancient, traditional and frankly elitist approach to imbibing knowledge than is a desire to maintain kudos and reputation. A case in point is the situation that my nephew found himself in throughout the first year of his study at a highly respected London university. It is accepted that making a transition from directed study at A-level to self-managed learning at university can be challenging but even as a top-grade A-level student who was nevertheless expecting his course to be difficult, so far, his 'university experience' has been an unhappy one. He feels that his earlier academic confidence has been substantially eroded because he has yet to find a route to the learning development and support from his academic tutors that he was expecting to be available and which he feels he needs if he is to make progress on his course. He has found the learning environment to be stale, unwelcoming, uncommunicative and isolationistic. He tells me that he considered giving up and leaving his course many times throughout the opening months and greatly regrets his choice of course and university despite these being, on paper at least, a good match for his academic interests and career aspirations. Although his may be an isolated case reported anecdotally, it may also be an indication of a wider malaise and reticence to engage more equitably with the contemporary university student who is choosing to invest in higher education. This seems inappropriate and unnecessarily challenging and if universities are to be part of an academically rigorous, tertiary education system that anyone with the right academic credentials can attend but which includes aspirations towards genuinely fostering social mobility, engendering social justice and meeting the learning development needs of its 'customers', then together with the maintenance of strong academic standards, a renewed effort should be devoted to finding ways to create a middle ground between possibly comptemptible student recruitement incentivization and an outdated, traditional, self-preserving learning orthodoxy. There must be an intermediate position that is properly developed, truly focuses on student-learning-centredness and provides a genuinely inclusive curriculum that everyone is able to engage with so that they are actively encouraged to aspire to their academic potential through the quality of their learning experience at university. Pockets of excellence do exist and these should be brought into the educational limelight with all haste as exemplars.

Learning diversity

Learning diversity

When challenged, or even driven by new legislation The Academy tackles issues of learning inclusivity through the minimal requirements to ensure compliance with 'reasonable adjustment' directives originally established in disability equality legislation now decades old. Adopting a ground-up reframing of academic curricula in ways that by design, embrace learning diversity appears to be outside the scope of strategic planning for the future of tertiary-level, high-quality learning - no doubt because it is considered radical, difficult and far too expensive. Despite this, some pockets of excellence really make a difference to some, if not all learners, demonstrated by those enlightened providers who look towards the adoption of elements of 'universal design' in the construction of university courses in which embracing learning diversities is at the core of curriculum processes (Passmann & Green, 2009). These are learning environments which place at the heart of their curricula the principle of giving all individuals equal opportunity to learn, the creation of learning goals, methods, materials and assessments that work for everyone and dispense with a 'one-size-fits-all' learning-and-teaching agenda in favour of flexible approaches that can be adapted and adjusted for individual needs (Jorgenson et al, 2013). However, attempts to create socially inclusive learning environments and opportunities tend to be inhibited by organizational factors (Simons et al, 2007) which can lead to a tokenist ‘nod’ being the more likely response to advocacy for genuinely making things (i.e. ‘learning’ in its broadest context) better for all participants in the knowledge community of university. More recently this position has been aggravated by an increased focus on accountability and quality of teaching at universities that has particularly created a tension in research-intensive institutions, especially where well-meaning campaigns for a reconfigured and more inclusive perception of 'scholarship' is nonetheless driving a wedge between teaching activities and research ones by lowering the status of teaching (MacFarlane, 2011). This is despite more recent research activities which have been concerned with identifying 'good teaching', quantifying what this means and presenting evidence that this is at the heart of high quality student learning (Trigwell, 2010).

The positive contributions to properly engaging with learning diversity in our universities that these initiatives are making seems patchy at best. In the face of sector-wide challenges ranging from widening participation to developing business-focused strategies that can respond to the government-imposed marketization of higher education (and the funding challenges that this is bringing), tackling the institutional entrenchment of traditional teaching and learning processes with a view to making the learning experience better for everyone and simultaneously striking a good balance between these activities and the essential job of universities to foster climates of research innovation and academic excellence, may be slipping further down the ‘to do’ list, not least because funding is uncertain and other initiatives aimed at providing alternatives to university are on the increase. Witness the diversity of current routes into teaching, most of which are eroding the essential value of academically-based initial training by attempting to develop rapid responses to a recruitment crisi,s that are at best, inappropriately thought through. Never are all these uncertainties more sorely felt than amongst communities of learners who come to university with spectra of learning profiles and preferences that are outside the box and as a result, often feel disenfranchised and not properly accommodated. For these individuals and groups whose learning needs fall outside the conventional envelope, broadly met by the existing ‘one-size-fits-all’ provision of higher education, the current processes of compensatory adjustments tend to apply strategies targeted at ‘fixing’ these unconventional learners – well-meaning as these may be – rather than focusing on the shortcomings of an outdated ‘system’ which originally evolved to serve the academic elite. These students are often labelled with difficult-to-define ‘learning disabilities’ and whatever these so-called ‘disabilities’ are, they are dynamic in nature, not necessarily an objective fact and that it is learning institutions that translate broad profiles of learning strengths and weaknesses into difficulties and disabilities through the strongly literacy-based medium of transmission of knowledge (Channock, 2007) and the lack of adaptability of this to learning differences.

The stance of this PhD project strongly advocates the belief that an overhaul of the processes for communicating knowledge through current, traditional curriculum delivery is well overdue, and also calls for a paradigm shift in the conventional assessment procedures that learners are required to engage with in order to express their ideas, demonstrate their intellectual competencies and foster the development of innovative thinking. With the focus of this research being ‘dyslexia’ – whatever this is, and which at the moment (Autumn 2017) remains labelled as a learning disability at university, I find myself uncomfortable with the disability label that is attached to the broad profile of learning differences and preferences apparently identifiable as a dyslexia, which is at variance with my strongly held views about embracing learning diversity. Whether someone has dyslexia or not wouldn’t matter – indeed, categorizing a particular set of learning profiles as a dyslexia would be inappropriate, unhelpful and unnecessary not least because in my ideal university, teaching, learning, assessment and access to resources would be offered in an equal variety of ways to match the learning diversities of those who choose to consume and contribute to knowledge environment at university. Everyone would feel included and properly accommodated.

The stance of this PhD project strongly advocates the belief that an overhaul of the processes for communicating knowledge through current, traditional curriculum delivery is well overdue, and also calls for a paradigm shift in the conventional assessment procedures that learners are required to engage with in order to express their ideas, demonstrate their intellectual competencies and foster the development of innovative thinking. With the focus of this research being ‘dyslexia’ – whatever this is, and which at the moment (Autumn 2017) remains labelled as a learning disability at university, I find myself uncomfortable with the disability label that is attached to the broad profile of learning differences and preferences apparently identifiable as a dyslexia, which is at variance with my strongly held views about embracing learning diversity. Whether someone has dyslexia or not wouldn’t matter – indeed, categorizing a particular set of learning profiles as a dyslexia would be inappropriate, unhelpful and unnecessary not least because in my ideal university, teaching, learning, assessment and access to resources would be offered in an equal variety of ways to match the learning diversities of those who choose to consume and contribute to knowledge environment at university. Everyone would feel included and properly accommodated.

The aim is that by exploring the relationship between the learning disability/difference of dyslexia and academic confidence the research objective is to establish that attributing a dyslexic label to a particular set of learning and study profiles can inhibit academic confidence and hence for the owner of this profile of attributes, contribute to a reduced likelihood of gaining strong academic outcomes. Academic confidence, through being a sub-construct of academic self-efficacy, is widely reported as a potential marker for academic performance (Honicke & Broadbent, 2016) and has been quantified in this project by using an existing measure of Academic Behavioural Confidence (Sander & Sanders, 2006) .

In short, when it comes to guiding learners towards getting a good degree at university, this project is testing the idea about whether is it better to label a so-called dyslexic person as ‘dyslexic’ or not.

If not, then in the first instance this would seem to indicate that dyslexic students, such as they are questionably defined, may be best left in blissful ignorance of their so-called ‘learning difference’ because if they are to have better prospects of gaining a higher academic outcome to their studies that is comparable to their non-dyslexic peers, they should be encouraged to battle on as best they can within the literacy-based system of curriculum delivery that they are studying in, despite it not being suited to their learning profiles, strengths and preferences. Hence there would be no recourse to ‘reasonable adjustments’ that identify them as ‘different’ because the identification itself might be more damaging to their academic prospects than the challenges they face that are considered attributable to their dyslexia. Secondly, this research outcome will add weight to my fundamental argument advocating a shift in ‘the system’ to one which embraces a much broader range of curriculum delivery and assessment as the most equitable means for establishing a level playing field upon which all students are able to optimize their academic functioning.

[1856 / 63,074 (at 08 Jan 2018)]

Research Importance

Research Importance

This study is important because it makes a major contribution towards filling a gap in research about dyslexia and academic confidence in the broader educational context of academic confidence as a sub-construct of academic self-efficacy and dyslexia as a learning difference in literacy-based education systems. Aside from two unpublished dissertations (Asquith, 2008, Barrett, 2005), no peer-reviewed studies have been found which specifically explore the impact that dyslexia may have on the academic confidence of learners in higher education. Asquith's study built on the earlier work by Barrett by investigating correlations between dyslexia and academic confidence using Sander & Sanders' (2006) Academic Behavioural Confidence Scale as an assessment tool for exploring academic confidence and Vinegrad's (1994) scale to gauge dyslexia. This study appears to be the only direct precursor of this current PhD project as it also sought to compare three undergraduate student groups: those with identified dyslexia, those with no indications of dyslexia and those who were possibly dyslexic. However this PhD project is the first to develop a fresh measure for identifying dyslexia-like study profiles that is not grounded in the deficit-model of dyslexia.

[187 /63,074 (at 08 Jan 2018)]

Theoretical Perspectives

1. Dyslexia

1. Dyslexia

A complex phenomenon or a psuedo-science?

Dyslexia - whatever it is - is complicated.

There is a persistent range of research methodologies and a compounding variety of interpretations that seek to explain dyslexia which continue to be problematic (Rice & Brooks, 2004). Attempts to theorize developmental dyslexia and its aetiology differ quite widely (Peterson & Pennington, 2015) not least when attempting to interpret the variety of characteristics that can be presented (Ramus, 2004). This is especially so in relation to how cognitive differences, more usually regarded as deficits, are classified as dysfunctions (Buttner & Hasselhorn, 2011) and whether these differences are causal, consequential or even covariants of the so-called learning disability (Vellutino et al, 2004). Hence, attributing any accurate, shared meaning to the dyslexic label that is helpful rather than confusing remains challenging at best. This is consistent with well over a century of research, postulation, commentary and narrative which has consistently failed to arrive at an end-point definition that can be ascribed to the dyslexia label (Smythe, 2011), and as long as learning outcomes based on high levels of literacy remain connected to intellect (MacDonald, 2009), learning barriers attributable to even a more positively-focused social construction of dyslexia are likely to remain, no matter how the syndrome is defined (Cameron & Billington, 2015).

Stanovich in particular has repeatedly questioned the discrepancy approach persistently used to measure dyslexia, insisting that when aptitude-achievement is used as the benchmark comparator, such a 'diagnosis' fails to properly discriminate between attributing poor reading abilities to dyslexia or to other typical causes (1988, 1991, 1993, 1996, 1999, 2000). Elliott & Grigorenko (2014) take this further in their argument that identifying dyslexia is problematic to the extent that assessments of it may be so flawed as to be irrelevant or at best, academically counter-productive. Notably, it has also been shown that students with so-called dyslexia in higher education may not be a homogeneous group due to the liklihood that several subtypes of dyslexia or dyslexia-like profiles may exist and hence that any identification approaches adopted, need to be designed to respond accordingly (Tops et al, 2012). These issues are explored below where the discussion specifically expands on the problems and suggested solutions surrounding the determination of the extent of a dyslexic individual's dyslexia - that is, how to assess the severity of dyslexia, or to more properly resonate with the stance of this project, to find out more about the levels of incidence of dyslexia-like characteristics in learning and study profiles and to understand how useful it may be to determine these in academic contexts.

Hence, given the persistent debate surrounding the nature of dyslexia and which aspects of the syndrome might be measurable and for what purpose, assigning a metric to establish a worthwhile appraisal of dyslexia, dyslexia-like characteristics or dyslexia-implied study profiles in learning context is ambitious. It is Stanovich's view that domain-specific difficulties - for example, finding reading challenging, struggling with arithmetic - may be comorbid in many cases, but it is only helpful to group such difficulties under an umbrella term - such as 'learning disabilty' (dyslexia in American) - after an initial domain-specific classification has been established (Stanovich, 1999, p350). This is significant not least because this argument adds weight to the adoption of a factorial view of dyslexia, especially in academically capable adult dyslexics where many of the early-years' learning difficulties may have been displaced by strategically developed learning solutions, leaving other dyslexia 'factors' as more influential in study processes at university. In the domain of adult learning at higher intellectually functional levels, that is in higher education, early-learning academic challenges are more often subsumed by later-learning organizational struggles that impact more substantially on learning confidence in comparison with earlier learning difficulties where processes are developed to circumvent earlier learning weaknesses often through widespread use of study aids (Kirby et al, 2008) and support agencies or technology (Olofsson et al, 2102).

It is significant therefore that relatively recent research interest is attempting to more fully understand subtypes of dyslexia. This builds on an idea first suggested by Castles and Coltheart (1993) who observed that there appeared to be evidence in developmental dyslexia of the subtypes more normally associated with acquired dyslexia - that is, through brain trauma. This suggests that there may be distinct dyslexia factors which may be more or less prevalent in any single individual who presents dyslexia or a dyslexia-like study and learning profile. More recent work has taken dyslexia in adults as a focus and particularly, students in higher education settings. Centred in The Netherlands, recent studies by Tamboer and colleagues in particular (eg: Tamboer et al, 2014) are taking the discussion in a new direction by building on the earlier research of Pennington (2006) and subsequently Le Jan et al (2009) by exploring more fully the factor structure of dyslexia to try to determine firstly whether understanding more about the subtypes of dyslexia can enable more effective screening tools to be developed for use in identifying the syndrome amongst university students, and secondly whether these are distinguishing features of dyslexic learners alone or that they can be observed to varying degrees in other, even all students. This approach in attempting to understand dyslexia and how it might be identified more specifically in tertiary education settings is particularly pertinent to my study and is considered in more detail below. First, an outline of the most significant endeavours to explain dyslexia are summarized.

Dyslexia: the definition issues

Frith (1999) tried to get to the nub of the definition problem by exploring three levels of description - behavioural, cognitive and biological - but still defined dyslexia as a neuro-biological disorder, speaking of controversial hypothetical deficits, and how these impact on the clinical presentation of dyslexia. The point here is that despite a courageous attempt to clearly provide a targeted explanation through an insightful analysis of the multifactoral impact of her three levels, this seminal paper still broadly concluded that 'undiagnosable' cultural and social factors together with (at the time) uncomprehended genetically-derived 'brain differences' persist in obfuscating a definitive conclusion. In his paper, Ramus (2004) took Frith's framework further, firstly by drawing our attention to the diversity of 'symptoms' (the preference in my paper here is to refer to a diversity of dimensions rather than 'symptoms' - more of this below) and subsequently confirming through his study that neurobiological differences are indeed at the root of phonological processing issues which is a characteristic that is often an early indication of a dyslexic learning difference, regularly observed. But more so, his study shed early light on these variances as an explanation for the apparent comorbidity of dyslexia with other neurodevelopmental disorders, often presented as sensory difficulties in many domains, for example, visual, motor control and balance, and others, which adds to the challenges in pinning dyslexia down. Although Ramus does not propose a single, new neurobiological model for dyslexia, more so suggests a blending of the existing phonological and magno-cellular theories (see below) into something altogether more cohesive, the claim is that evidence presented is consistent with results from research studies in both camps to date, and so is quite weighty. Fletcher (2009), in trying to bring together a summary of more recent scientific understanding of dyslexia, attempts to visualize the competing/contributory factors that can constitute a dyslexic profile in a summary diagram which is helpful.

[adapted from Fletcher, 2009, p511]

Fletcher adds a dimension to those previously identified by Frith, Ramus, et al by factoring in environmental influences, not least of which includes social aspects of learning environments which may be some of the most impacting factors on learning identity. Mortimore & Crozier (2006) demonstrated that acceptance of dyslexia as part of their learning identity was often something that students new to university were unwilling to embrace, often because they felt that the 'fresh start' of a tertiary educational opportunity would enable them to adopt other, more acceptable social-learning identities that were deemed more inviting. This conclusion is supported by one respondent in the current research project who reflected on their dyslexia hence:

- "I don't really like feeling different because people start treating you differently. If they know you have dyslexia, they normally don't want to work with you because of this ... I am surprised I got into university and I am where I am ... and I find it very hard [so] I don't speak in class in case I get [questions] wrong and people laugh" (respondent #85897154, available at: http://www.ad1281.uk/phdQNRstudentsay.html )

This illuminates aspects of dyslexia which impact on the identity of the individual in ways that mark them as different -in learning contexts at least - and is an important element that will be discussed below.

Other explanations rooted in physiology, notably genetics, have encouraged some further interest, notably a paper by Galaburda et al (2006) who claimed to have identified four genes linked to developmental dyslexia following research with rodents, and a more recent study which was concerned with identifying 'risk genes' in genetic architecture (Carion-Castillo et al, 2013). However, scientific as these studies may have been, their conclusions serve as much to prolong the controversy about how to define dyslexia rather than clarify what dyslexia is because these studies add yet another dimension to the dyslexia debate.

Sensory differences is an explanation that has attracted support from time to time and attributes the manifestations of dyslexia most especially to visual differences - the magnocellular approach to defining dyslexia (Evans, 2003 amongst many others). Whilst there is no doubt that for many, visual stress can impair access to print, this scotopic sensitivity, more specifically referred to as Meares-Irlen Syndrome (MIS), may be a good example of a distinct but co-morbid condition that sometimes occurs alongside dyslexia rather than is an indicator of dyslexia. Later research by Evans & Kriss (2005) accepted this comorbidity idea and found that there was only a slightly higher prevalence of MIS in the individuals with dyslexia in their study in comparison to their control. Common in educational contexts to ameliorate vision differences, especially in universities, there is a long-standing recommendation for tinted colour overlays to be placed on hard-copy text documents, or assistive technologies that create a similar effect for electronic presentation of text. But evidence that this solution for remediating visual stress is more useful for those with dyslexia than for everyone else is sparse or contrary (eg: Henderson et al, 2013) or as one study found, can actually be detrimental to reading fluency, particularly in adults (Denton & Meindl, 2016). So although the relationship between dyslexia and visual stress remains unclear, there is evidence to indicate that there is an interaction between the two conditions which may have an impact on the remediation of either (Singleton &Trotter, 2005).

Sensory differences is an explanation that has attracted support from time to time and attributes the manifestations of dyslexia most especially to visual differences - the magnocellular approach to defining dyslexia (Evans, 2003 amongst many others). Whilst there is no doubt that for many, visual stress can impair access to print, this scotopic sensitivity, more specifically referred to as Meares-Irlen Syndrome (MIS), may be a good example of a distinct but co-morbid condition that sometimes occurs alongside dyslexia rather than is an indicator of dyslexia. Later research by Evans & Kriss (2005) accepted this comorbidity idea and found that there was only a slightly higher prevalence of MIS in the individuals with dyslexia in their study in comparison to their control. Common in educational contexts to ameliorate vision differences, especially in universities, there is a long-standing recommendation for tinted colour overlays to be placed on hard-copy text documents, or assistive technologies that create a similar effect for electronic presentation of text. But evidence that this solution for remediating visual stress is more useful for those with dyslexia than for everyone else is sparse or contrary (eg: Henderson et al, 2013) or as one study found, can actually be detrimental to reading fluency, particularly in adults (Denton & Meindl, 2016). So although the relationship between dyslexia and visual stress remains unclear, there is evidence to indicate that there is an interaction between the two conditions which may have an impact on the remediation of either (Singleton &Trotter, 2005).

An alternative viewpoint about the nature of dyslexia is represented by a significant body of researchers who take a strong position based on the notion of 'neuro-diversity'. The BRIAN.HE project (2005), now being revised but with many web resources still active and available, hailed learning differences as a natural consequence of human diversity. Pollak's considerable contribution to this thesis about dyslexia, both through the establishment of BRIAN.HE and notably drawn together in a collection of significant papers (Pollak, 2009), expounds the idea that dyslexia is amongst so-called 'conditions' on a spectrum of neuro-diversity which includes, for example, ADHD and Asperger's Syndrome. Particularly this view supports the argument that individuals with atypical brain 'wiring' are merely at a different place on this spectrum in relation to those others who are supposedly more 'neurotypical'. The greater point here is elegantly put by Cooper (2006), drawing on the social-interactive model of Herrington & Hunter-Carch (2001), and this is the idea that we are all neurodiverse and that it remains society's intolerance to differences that conceptualizes 'neurotypical' as in the majority. This may be particularly apparent in learning contexts where delivering the curriculum through a largely inflexible literacy-based system discriminates against particular presentations of neurodiversity (eg: Cooper, 2009).

So defining dyslexia as a starting point for an investigation is challenging. This causes problems for the researcher because the focus of the study ought to be supported by a common understanding about what dyslexia means because without this, it might be argued that the research outcomes are relational and definition-dependent rather than absolute. However, given the continued controversy about the nature of dyslexia, it is necessary to work within this relatively irresolute framework and nevertheless locate the research and the results and conclusions of the research accordingly.

What seems clear and does seem to meet with general agreement, is that at school-age level, difficulties experienced in phonological processing and the 'normal' development of word recognition automaticity appear to be the root causes of the slow uptake of reading skills and associated challenges with spelling. Whether this is caused by a dyslexia of some description or is simply unexplained poor reading may be difficult to determine. Setting all other variables aside, a skilful teacher or parent will notice that some children find learning to read particularly challenging and this will flag up the possibility that these learners are experiencing a dyslexia.

What also seems clear, is that for learners of above average academic ability but who indicate dyslexia-associated learning challenges - in whatever way both of these attributes are measured - it is reasonable to expect these learners to strive to extend their education to post-secondary levels along with everyone else in their academic peer groups, despite the learning challenges that they face as a result of their learning differences. Amongst many other reasons which include desire for improved economic opportunities resulting from success at university, one significant attraction of higher education is a desire to prove self-worth (Madriaga, 2009). An analysis of HESA data bears out the recent surge in participation rates amongst traditionally under-represented groups at university of which students with disabilities form one significant group (Beauchamp-Prior, 2013). There is plenty of recent research evidence to support this which relates to students entering university with a previously identified learning difference and this will be discussed more fully in the final thesis. But a compounding factor which suggests an even greater prevalence of dyslexia at university beyond data about dyslexic students on entry is indicated through the rising awareness of late-identified dyslexia at university. This is evidenced not the least through interest in creating screening tools such as the DAST (Dyslexia Adult Screening Test, Fawcett & Nicholson, 1998) and the LADS software package (Singleton & Thomas, 2002) to name just two technology-based items which will be discussed further, below. But this is also a measure of the recurring need to develop and refine a screening tool that works at university level which takes more interest in the other learning challenges as additional identifying criteria rather than persist with assessing largely literacy-based skills and the relationship of these to perhaps, speciously-defined, measures of 'intelligence'. This is also discussed a little more and in the context of this paper, below.

Recent thinking: describing dyslexia using a multifactoral approach

[key papers to report on here: Tamboer et al, 2014 'Five describing factors of dyslexia'; (Castles & Coltheart, 1992, 'Varieties of developmental dyslexia'); Pennington, 2006, 'From single to multiple deficit models of developmental disorders'; Le Jan et al, 2011, 'Multivariate predictive model for dyslexia diagnosis']

Disability, deficit, difficulty, difference or none of these?

With the exception of Cooper's description of dyslexia being an example of neuro-diversity rather than a disability, difficulty or even difference, definitions used by researchers and even professional associations such as the British Dyslexia Association, Dyslexia Action, The Dyslexia Foundation, The International Dyslexia Association, The American Dyslexia Association, all tend to remain focused on the issues, challenges and difficulties that dyslexia presents for individuals engaging with learning that is delivered through conventional curriculum processes. This approach tacitly compounds the 'adjustment' agenda which is focused on the learner rather than the learning environment.

'Difficulty' or 'disorder' are both loaded with negative connotations that imply deficit, particularly within the framework of traditional human learning experiences in curriculum delivery environments that do remain almost entirely 'text-based'. This is despite the last decade or two of very rapid development of alternative, technology or media-based delivery platforms that have permeated western democracies and much of the alternative and developing worlds. This 'new way' is embraced by an information society that sees news, advertising, entertainment and 'gaming', government and infrastructure services, almost all aspects of human interaction with information being delivered through electronic mediums. And yet formal processes of education by and large remain steadfastly text-based which, although now broadly delivered electronically, still demand a 'conventional' ability to properly and effectively engage with the 'printed word' both to consume knowledge and also to create it. This persistently puts learners with dyslexia - in the broadest context - and with dyslexia-like learning profiles at a continual disadvantage and hence is inherently unjust. An interesting, forward-looking paper by Cavanagh (2013) succinctly highlights this tardiness in the delivery of education and learning to keep up with developments in information diversity and candidly observes that the collective field of pedagogy and andragogy should recognize that, rather than learners, it is curricula that is disabled and hence, needs be fixed – a standpoint that resonates with the underlying rationale that drives this PhD Project.

'Difficulty' or 'disorder' are both loaded with negative connotations that imply deficit, particularly within the framework of traditional human learning experiences in curriculum delivery environments that do remain almost entirely 'text-based'. This is despite the last decade or two of very rapid development of alternative, technology or media-based delivery platforms that have permeated western democracies and much of the alternative and developing worlds. This 'new way' is embraced by an information society that sees news, advertising, entertainment and 'gaming', government and infrastructure services, almost all aspects of human interaction with information being delivered through electronic mediums. And yet formal processes of education by and large remain steadfastly text-based which, although now broadly delivered electronically, still demand a 'conventional' ability to properly and effectively engage with the 'printed word' both to consume knowledge and also to create it. This persistently puts learners with dyslexia - in the broadest context - and with dyslexia-like learning profiles at a continual disadvantage and hence is inherently unjust. An interesting, forward-looking paper by Cavanagh (2013) succinctly highlights this tardiness in the delivery of education and learning to keep up with developments in information diversity and candidly observes that the collective field of pedagogy and andragogy should recognize that, rather than learners, it is curricula that is disabled and hence, needs be fixed – a standpoint that resonates with the underlying rationale that drives this PhD Project.

Cavanagh is one of the more recent proponents of a forward-facing, inclusive vision of a barrier-free learning environment - the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) – which as a 20-year-old 'movement' originating from a seminal paper by Rose & Meyer (2000) is attempting to tackle this issue in ways that would declare dyslexia to be much more widely recognized as, at worst, a learning difference amongst a plethora of others, rather than a learning difficulty or worse, disability. With its roots in the domain of architecture and universal accessibility to buildings and structures, the core focus of UDL is that the learning requirements of all learners are factored into curriculum development and delivery so that every student's range of skills, talents, competencies and challenges are recognized and accommodated without recourse to any kind of differentiated treatment to 'make allowances'. Hence it becomes the norm for learning environments to be much more easily adaptable to learners' needs rather than the other way around. This will ultimately mean that text-related issues, difficulties and challenges that are undoubted deficits in conventional learning systems cease to have much impact in a UDL environment. There is an increasing body of evidence to support this revolution in designing learning in this way, where researchers persistently draw attention to the learning-environment challenges facing different learners, ranging from equitable accommodation into the exciting new emphasis on developing STEM education (eg: Basham & Marino, 2013) to designing learning processes for properly including all students into health professions courses (eg: Heelan, et al, 2015).

Other measures are still required to ensure an element of equitability in learning systems that fail to properly recognize and accommodate learning diversity. Extensive earlier, and recently revisited research on learning styles has demonstrated (not unsurprisingly) that when teaching styles are aligned with student learning styles, the acquisition and retention of knowledge and more so, how it is subseqently re-applied, is more effective and fosters better learning engagement (Felder, 1988, Zhou, 2011, Tuan, 2011, Gilakjani, 2012) and that a mismatch between teaching and learning styles can cause learning failure, frustration and demotivation (Reid, 1987, Peacock, 2001). For example, preferences towards knowledge being presented visually is demonstrable in many dyslexic learners (Mortimore, 2008). There are arguments to support a neuro-biological explanation for this apparent preference which is based on investigations of the periphery-to-centre vision ratio metric. This describes the degree of peripheral vision bias in individuals' vision preferences and research evidence suggests that this is high in many people with dyslexia (Schneps et al, 2007) which means that many dyslexics evidence a preference towards favouring the peripheral vision field over the centre (Geiger & Lettvin, 1987). Ironically, this may also account for deficits in information searching capabilities often observable in many with dyslexia because accuracy in this activity relies on good centre-vision focus (Berget, 2016), it also may explain greater incidence of more acute visual comparative abilities and talents often associated with dyslexia. In learning environments this may be particularly significant where interrelationships between concepts are complex and would otherwise require lengthy textual explanations to clearly present meaning. Not least this is sometimes due to a comorbidity of dyslexia with attention deficit disorder where the dyslexic reader may experience difficulty in isolating key ideas or be easily distracted from, or find increasing difficulty in engaging with the reading task (Goldfus, 2012, Garagouni-Areou & Solomonidou, 2004) or simply find reading exhausting (Cirocki, 2014). Dyslexic learners often get lost in the words. However another detailed study of learning style preferences in adolescents which adopted the Visual-Auditory-Kinestetic learning styles model as the means for acquiring data revealed no significant differences between the learning styles of dyslexic participants and those with no indication of dyslexia although the research did demonstrate that dyslexic learners present a greater variety of learning style preferences than their non-dyslexic peers (Andreou & Vlachos, 2013). This is an interesting result which might be explained by suggesting that learning frustration experienced by more academically able dyslexic learners in attempting to engage with learning resources which, to them at least, present access challenges, is compensated by developing alternative learning strategies and styles which they match to meet the demands of learning situations as they are encountered. Many other studies in recent years have explored relationships between dyslexia and learning styles although conclusions reached appear mixed. For example, in the cohort of 117 university students with dyslexia used in Mortimore's (2003) study, no link was established between any preference for visuo-spatial learning styles and dyslexia which may seem unexpected in the light of other research suggesting that one of the characteristizing aspects of dyslexia can be elevated visuo-spatial abilities in certain circumstances (Attree et al, 2009). Indeed, common knowledge in professional practice in university level support for dyslexic students regularly advocates and provides assistive learning technologies that are designed to make learning more accessible for those with visual learning strengths. This continues to be a central provision of technology support for dyslexic students in receipt of the (UK) Disabled Students' Allowance . Searching for alternative means to provide easier access to learning for dyslexic students appears to have spawned other, interesting studies. For example, Taylor et al (2009) developed innovative animated learning materials, hoping to show that these provided improved learning access for students with dyslexia. However the outcome of the study showed that their animations were of equal learning value to both dyslexic and non-dyslexic students and attempted to explain this by suggesting that as with other forms of learning resources, non-dyslexic students typically find these easier to access than their dyslexic peers.

Labels, categories, dilemmas of difference, inclusivity

[introduce this section drawing on the seminal work by Minow M, 1991, 'Making all the difference' that set out the broad framework in the inclusion/exclusion debate for accommodating difference as the most valuable and meaningful 'label']

There are many well-rehearsed arguments that have sought to justify the categorization of learners as a convenient exercise in expediency that is generally justified as essential for establishing rights to differentiated 'support' as the most efficacious forms of intervention (Elliott & Gibbs, 2008). This is support which aims to shoe-horn a learner labelled with 'special needs' into a conventional learning box, by means of the application of 'reasonable adjustments' as remediative processes to compensate for learning challenges apparently attributed to their disability.

There are many well-rehearsed arguments that have sought to justify the categorization of learners as a convenient exercise in expediency that is generally justified as essential for establishing rights to differentiated 'support' as the most efficacious forms of intervention (Elliott & Gibbs, 2008). This is support which aims to shoe-horn a learner labelled with 'special needs' into a conventional learning box, by means of the application of 'reasonable adjustments' as remediative processes to compensate for learning challenges apparently attributed to their disability.

Outwardly, this is neat, usually well-meaning, ticks boxes, appears to match learner-need to institutional provision, and apparently 'fixes' the learner in such a way as to level the academic playing field so as to reasonably expect such learners to 'perform' in a fair and comparable way with their peers. Richardson (2009) reported on analysis of datasets provided by HESA that this appears to work for most categories of disabled learners in higher education, also demonstrating that where some groups did appear to be under-performing, this was due to confounding factors that were unrelated to their disabilities.

However some researchers claim that such accommodations can sometimes positively discriminate, leading to unfair academic advantage because the 'reasonable adjustments' that are made are somewhat arbitrarily determined and lack scientific justification (Williams & Ceci, 1999). Additionally, there is an interesting concern that many students who present similar difficulties and challenges when tackling their studies to their learning-disabled peers but who are not officially documented through a process of assessment or identification (that is, diagnosis) are unfairly denied similar access to corresponding levels of enhanced study support. It is exactly this unidentified learning difference that the metric in this research study is attempting to reveal and the development of which is described in detail below. Anecdotal evidence from this researcher's own experience as an academic guide in higher education suggests that at university, many students with learning differences such as dyslexia have no inkling of the fact, which is supported by evidence (for example) from a survey conducted in the late 90s which reported that 43% of dyslexic students at university were only identified after they have started their courses (National Working Party on Dyslexia in HE, 1999).  Indeed it has also been reported that some students, witnessing their friends and peers in possession of newly-provided laptops, study-skills support tutorials and extra time to complete their exams all provided through support funding, go to some lengths to feign difficulties in order to gain what they perceive to be an equivalent-to-their-friends, but better-than-equal academic advantage over others not deemed smart enough to play the system (Harrison et al, 2008, Lindstrom et al, 2011).

Indeed it has also been reported that some students, witnessing their friends and peers in possession of newly-provided laptops, study-skills support tutorials and extra time to complete their exams all provided through support funding, go to some lengths to feign difficulties in order to gain what they perceive to be an equivalent-to-their-friends, but better-than-equal academic advantage over others not deemed smart enough to play the system (Harrison et al, 2008, Lindstrom et al, 2011).

But there is some argument to suggest that, contrary to dyslexia being associated with persistent failure (Tanner, 2009), attaching the label of dyslexia to a learner - whatever dyslexia is - can be an enabling and empowering process at university exactly because it opens access to support and additional aids, especially technology which has been reported to have a significantly positive impact on study (Draffan et al, 2007). Some researchers who investigated the psychosocial impacts of being designated as dyslexic have demonstrated that embracing their dyslexia enabled such individuals to identify and use many personal strengths in striving for success, in whatever field (Nalavany et al, 2011). In taking the neurodiversity approach however, Grant (2009) points out that neurocognitive profiles are complicated and that the identification of a specific learning difference might inadvertently be obfuscated by a diagnostic label, citing dyslexia and dyspraxia as being very different situations but which share many similarities at the neurocognitive level. Ho (2004) argued that despite the 'learning disability' label being a prerequisite for access to differentiated provision in learning environments and indeed, civil rights protections, these directives and legislations have typically provided a highly expedient route for officialdom to adopt the medical model of learning disabilities and pay less attention or even ignore completely other challenges in educational systems. 'Learning disabilities' (LD) is the term generally adopted in the US, broadly equivalent to 'learning difficulties' everywhere else, of which it is generally agreed that 'dyslexia' forms the largest subgroup; and the legislation that is relevant here is enshrined in the UK in the Disability Discrimination Act, later followed by the Disability Equality Duty applied across public sector organizations which included places of learning, all replaced by the Equality Act 2010 and the Public Sector Equality Duty 2011. So one conclusion that may be drawn here is that as long as schools, and subsequently universities persist in relying heavily on reading to impart and subsequently to gain knowledge, and require writing to be the principal medium for learners to express their ideas and hence for their learning to be assessed, pathologizing the poor performance of some groups of learners enables institutions to avoid examining their own failures (Channock, 2007).

Other arguments focus on stigmatization associated with 'difference':

On the disability agenda, many studies examine the relationship between disability and stigma with several drawing on social identity theory. For example, Nario-Redmond et al (2012) in a study about disability identification outlined that individuals may cope with stigma by applying strategies that seek to minimize stigmatized attributes but that often this is accompanied by active membership of stigmatized groups in order to enjoy the benefit of collective strategies as a means of self-protection. Social stigma itself can be disabling and the social stigma attached to disability, not least given a history of oppression and unequal access to many, if not most of society's regimens, is particularly so. Specifically in an education context, there is not necessarily a connection between labels of so-called impairment and the categorization of those who require additional or different provision (Norwich, 1999). Indeed, there is a significant body of research that identifies disadvantages in all walks of life that result from the stigmatization of disabilities (eg: McLaughlin, et al, 2004, Morris & Turnbill, 2007, Trammel, 2009). Even in educational contexts and when the term is arguably softened to 'difficulties' or even more so to 'differences', the picture remains far from clear with one study (Riddick, 2000) suggesting that stigmatization may already exist in advance of labelling, or even in the absence of labelling at all. Sometimes the stigma is more associated with the additional, and sometimes highly visible, learning support - students accompanied by note-takers for example - designed to ameliorate some learning challenges (Mortimore, 2013) with some studies reporting a measurable social bias against individuals with learning disabilities who were perceived less favourably than their non-disabled peers (eg: Tanner, 2009, Valas, 1999,). This was not the least also evidenced from the qualitative data that has been collected in this current research project which will be more deeply analysed later, however an example presented here is representative of many similar others that were received:

Other arguments focus on stigmatization associated with 'difference':

On the disability agenda, many studies examine the relationship between disability and stigma with several drawing on social identity theory. For example, Nario-Redmond et al (2012) in a study about disability identification outlined that individuals may cope with stigma by applying strategies that seek to minimize stigmatized attributes but that often this is accompanied by active membership of stigmatized groups in order to enjoy the benefit of collective strategies as a means of self-protection. Social stigma itself can be disabling and the social stigma attached to disability, not least given a history of oppression and unequal access to many, if not most of society's regimens, is particularly so. Specifically in an education context, there is not necessarily a connection between labels of so-called impairment and the categorization of those who require additional or different provision (Norwich, 1999). Indeed, there is a significant body of research that identifies disadvantages in all walks of life that result from the stigmatization of disabilities (eg: McLaughlin, et al, 2004, Morris & Turnbill, 2007, Trammel, 2009). Even in educational contexts and when the term is arguably softened to 'difficulties' or even more so to 'differences', the picture remains far from clear with one study (Riddick, 2000) suggesting that stigmatization may already exist in advance of labelling, or even in the absence of labelling at all. Sometimes the stigma is more associated with the additional, and sometimes highly visible, learning support - students accompanied by note-takers for example - designed to ameliorate some learning challenges (Mortimore, 2013) with some studies reporting a measurable social bias against individuals with learning disabilities who were perceived less favourably than their non-disabled peers (eg: Tanner, 2009, Valas, 1999,). This was not the least also evidenced from the qualitative data that has been collected in this current research project which will be more deeply analysed later, however an example presented here is representative of many similar others that were received:

- "When I was at school I was told that I had dyslexia. When I told them I wanted to be a nurse [and go to university], they laughed at me and said I would not achieve this and would be better off getting a job in a supermarket" (respondent #48997796, available here)

Similar evidence relating to social bias was recorded by Morris & Turnbill (2007) through their study exploring the disclosure of dyslexia in cohorts of students who successfully made it to university to train as nurses, although it is possible that their similar conclusions to these other studies were confounded by nurses' awareness of workplace regulations relating to fitness to practice. This aspect of disclosure-reluctance has been mentioned earlier. It has also been recorded that the dyslexia (LD) label might even produce a differential perception of future life success and other attributes such as attractiveness or emotional stability despite such a label presenting no indication whatsoever about any of these attributes or characteristics (Lisle & Wade, 2014). Perhaps the most concerning, is evidence that parents and especially teachers may have lower academic expectations of young people attributed with learning disabilities or dyslexia based on a perceived predictive notion attached to the label (Shifrer, 2013, Hornstra et al, 2014) and that in some cases, institutional processes have been reported to significantly contribute to students labelled as 'learning-disabled' choosing study options broadly perceived to be less academic (Shifrer et al, 2013).